Tailgate Talk Across America — On College Value, Diversity, and AI

This year has been searing for U.S. colleges and universities — from grappling with federal funding cuts to rancor over diversity programs to the ultimate value of college amid an affordability crisis and the rise of AI.

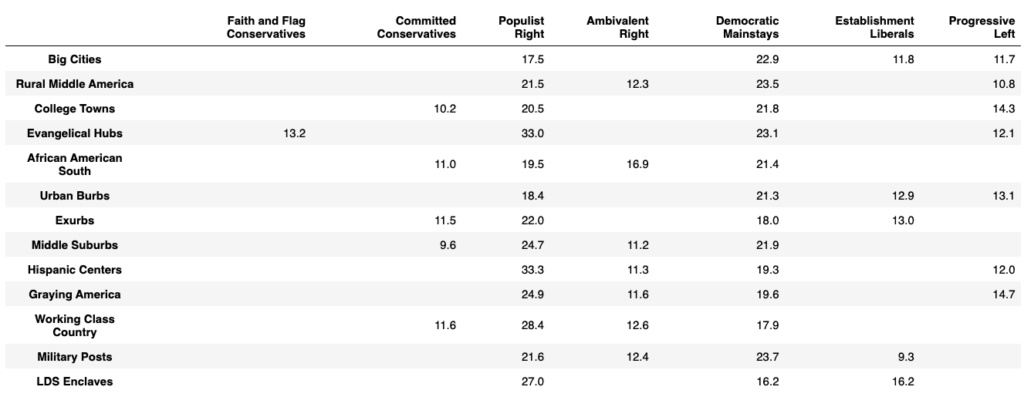

Still, most people said a college degree is somewhat or very important for a good life, according to the American Communities Project/Ipsos American Fragmentation survey of some 5,000 Americans conducted in August 2025. There is some variance at the community level, with a high mark of 87% in the diverse and densely populated Big Cities, full of white-collar professionals.

In the very rural communities, residents see the value differently: 53% in Native American Lands and 31% in Aging Farmlands said, “Earning a bachelor’s degree is important to a person’s ability to have a good life.”

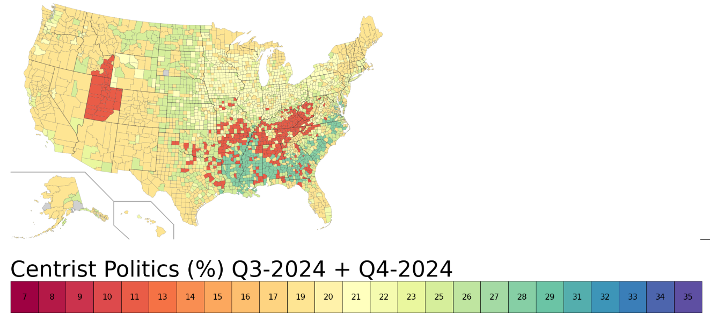

On other issues affecting colleges and universities, there is more of a split, according to the ACP/Ipsos survey. For the 90% of Americans familiar with generative AI platforms, such as ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot, and Gemini, 47% said they use these at least every two weeks. Less hope surfaces when considering AI’s potential future impacts on daily life, livelihoods, and children. Meanwhile, diversity programs are not widely popular. Just 40% said, “The U.S. should do more to level the playing field for historically underrepresented groups.” In Big Cities, 56% said so; it’s the only community type above 50%. (Explore views on AI and other major issues from the ACP’s latest survey.)

To understand what’s behind the numbers, the ACP enlisted writers from coast to coast to interview fans at college football tailgates about the value of college, their views on diversity programs, their thoughts about the Trump administration’s involvement in higher education operations, and their biggest hopes and fears for artificial intelligence. These interviews deepened the ACP’s survey results. Attendees detailed college’s holistic worth and high cost but divided over diversity programs as well as President Trump’s intervention. They shared excitement over AI’s efficiency, empowering quality, and scientific advances alongside worries about privacy, trust, job loss, and critical-thinking atrophy.

In such unsettlement, the tailgates consistently played out with a sense of joy in community. “Sports” as “a place of social connection, community, and entertainment” was also highlighted in a recent survey of some 3,100 adults, sponsored by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. (Click on the anchor links below for ACP vignettes at college football tailgates this fall.)

- Villanova University in Delaware and Montgomery counties, PA (Urban Suburbs)

- Howard University in Washington, DC (Big City)

- Michigan State University in Ingham County, MI (College Town)

- The University of New Mexico in Bernalillo (Big City), Los Alamos (Exurb), McKinley (Native American Land), Taos (Hispanic Center), and Valencia, NM counties (Hispanic Center)

- Montana State University in Gallatin County, MT (College Town)

- Brigham Young University in Utah County, UT (LDS Enclave)

- University of California–Los Angeles in Los Angeles County, CA (Big City)

Villanova University in Delaware and Montgomery counties, PA (Urban Suburbs)

By Ari Pinkus

Villanova University’s first Tailgate on the Green this season — aka Family Weekend — was a bright bubble of blue and white all over, students and their families packed under a couple hundred 10’x10’ neatly aligned tents brimming with sandwiches, tomato pies, and baked goods. This field of school spirit saw children playing cornhole on the grass, longtime friends reuniting, student band members drumming, and even the cops on patrol engaging. These multigenerational, mostly white fans were gearing up to cheer on Villanova’s Wildcats against William & Mary’s Tribe. On this football Saturday, September 27, the foliage was falling, welcoming fall to the 260-acre campus along the historic Main Line, just 12 miles from Philadelphia.

The tailgate on Mendel Field; nearby landmark statue of Gregor Johann Mendel, the father of genetics and Abbot of the Augustinian Monastery; and plaque of Mendel Medal recipients recognizing “scientific accomplishment and religious conviction” all convey the vitality of science and religion on campus and beyond. Founded in 1842 by the Order of Saint Augustine, Villanova University sees its Augustinian roots continuing to branch out. The recently installed Pope Leo XIV graduated from Villanova with a degree in mathematics in 1977. He became a friar in the Order of Saint Augustine later that year. That Pope Leo is an alumnus elicits deep pride here.

According to Main Liners who grew up in the 1970s, Villanova was known for being full of suitcase commuters and supporting pluralism. Its current physical plant and $1.4 billion endowment tell a story of investment and growth. It’s leveraged its business program and law school and developed its men’s basketball team to blue-blood status. The Wildcats have won three NCAA championships, most recently in 2018.

At Tailgate on the Green, Villanova students’ parents and grandparents radiated pride and credited their college educations with enhancing their knowledge, opportunity, and agency, even as they shared concerns about changes roiling the field.

Value of College in Life

Nancy Earley attended the tailgate with her husband, Frank, to support their daughter, a freshman here. Coming from Westchester County, New York, Nancy expressed surprise over how beautiful and well-organized the setting was. College, she said, means so much to her because of her parents’ struggles. “I always grew up knowing I would want to go to college, so I don’t really know an alternative path, but I’m first generation,” she said. “So, my parents had it instilled from very early on that I was going, because I think they lived the other side of trying to grow without having an education, trying to start at the bottom, really, no paperwork to that door. So, it was really them motivating me to go.”

For Frank, the social ties he forged in college remain strong. “I talk to my friends from college every day. I played football so that was a bond. We do business together.” Both were quick to say they use their college educations every day, Nancy as an elementary school teacher who graduated from Marist University, and Frank as a lawyer who earned his bachelor’s from the University of Rochester.

Sachin Shah, who graduated from Villanova’s combined BS/MD program in 1995, has a very different background. Born in India, he immigrated to the U.S. as an infant, growing up primarily in New Jersey. For Dr. Shah, college expanded his interests and understanding. “When getting an advanced degree, like an MD, of course I had to go to college. I had to get all the prerequisites done and get the bachelor’s degree. It was a fun time, not only with the science classes I took, but I was able to take other philosophy, religion, liberal arts classes that I enjoyed tremendously. … I did an MBA as well, so it was sort of different than my medical training, but that also was very enjoyable. See a different part of life, different field in the world.” Socially, he had a blast, he said. “I think probably medical school and ultimately residency is where I formed my closest friends, just because it’s such a common life, common goals, common interests.”

Residency is where Shah met his wife. The couple drove about two hours from their Connecticut home to tailgate with their son and a bunch of friends. “In terms of tailgating, it’s my first time back since I graduated because my son is now a freshman here.”

Sitting on a bench next to the field was David Hornyak, a 76-year-old retired businessman who flew in from Pittsburgh to tailgate with his granddaughter, a student here. “This is the first tailgate party that I’ve seen,” he said.

College has enriched Hornyak’s life, but he questions the value of a liberal arts focus. He majored in accounting and graduated from Duquesne University in 1971. “Never spent one day in accounting. I had my own business after that. So, I guess it helped me out, in retrospect, but really not in the field that I started out.”

Hornyak relishes the lifelong friends he made in college. “I just got off the phone with one. Duquesne is a relatively small college, and we still get together occasionally.”

The U.S. President in Higher Ed Institutions

President Trump’s involvement in the operations of colleges and universities drew a mix of views. Nancy Earley said, “I think it has no place in universities,” adding that she doesn’t want “any type of government oversight in what you’re teaching. Curriculum should be set based on history and values in common, not dictated by one person or group.”

Her husband, Frank, underscored the point. “It’s the opposite of the Republican Party, small government, independence, right?”

Shah conveyed a layered perspective. “I don’t agree with all of what [President Trump’s] pushing. Trying to dictate what [Harvard] teaches, what they don’t teach, I don’t think that’s appropriate, certainly. But I think there absolutely needed to be a reckoning. … Depending on the school, you’re talking single digits of the quote, unquote conservative or right-leaning viewpoint. I think that’s a big detriment,” he said.

Diversity Programs

On another hot-button topic, diversity programs at colleges, Shah opened up: “I struggle with them. I absolutely understand the benefits of a diverse viewpoint, but I think to have quotas, to say you’re picking one group or one student over another just because of their background, or just because you think they’re underprivileged or underrepresented, I have a big problem with that. I believe in meritocracy, and unfortunately, more and more in the medical field, I’m not seeing the quality that I used to, and I admit that it might be just bias, an age bias, you know, it’s much tougher when I did it. But I do think in the medical field, it’s going to catch up to us in a negative way.”

In Shah’s mind, diversity programs can cut against their intent. “It’s unfair for the minority group, because then I think the first thing people think of is, oh, the only reason you’re in that position is because of X or Y, not because you deserved it, not because you achieved your goals, and were an excellent candidate.”

Frank Earley is OK with the idea of these programs in general, but he admits they haven’t affected him or changed his workplace. “Diversity programs are important as long as they’re done right. I have good friends who are diversity officers at huge corporations and professional athletic leagues, and they’re important… You have to give people a chance.”

Hopes and Fears Around AI

What will artificial intelligence bring to education, workplaces, and society as the future unfolds? For his part, Frank Earley is most excited about AI’s efficiency. “It’s amazing; it’s instantaneous. I use it every day. I don’t always know it’s right, but I know it’s in a range. And it’s a great starting point. … I do research, and I give it to the young lawyers to make sure I was right.”

But concerns quickly surface, too. “The biggest fear for us is how you keep learning the right way. So as a lawyer, writing is 90% of what you do, and now you don’t have to do it. It does it for you,” he said. “How do you actually get the baseline training to where you can be that next level? That’s something we talk about.”

Longer-term, Frank wonders how AI will affect his children’s futures. Their daughter aspires to be a doctor while their son is studying physics engineering. “Am I worried about it taking over the world? I’m not smart enough to know that answer, but I do have concerns about what’s going to happen with young people getting jobs,” Frank said. “And are you going to need those entry-level people anymore?”

His wife, Nancy, said her elementary students are using AI now. “They’re young, so we’re teaching them that you have to vet anything that comes by you. Where does it come from? Who cultivated it? Where are they pulling from? But everybody has to get better, or [AI] has no value.”

For Shah, AI is a boon — and soon a necessity. “I’m more hopeful than fearful. I see how it helps our field already, and I think the people that embrace it and understand how to use it are the ones that are going to be employed and whatnot.”

Shah noted that while it won’t be a smooth adoption, AI will bring mass progress. “I think, unfortunately, there’s definitely going to be upheaval and disruption, but at the end of it, I think it’s going to be tremendous in terms of new medical discoveries, new engineering, biotech, economic policy.”

Efficiency is top of mind for Shah, too. “I think it’ll save a lot of time and really help us achieve our goals much faster than maybe right now.” He uses AI peripherally in his work now — and looks forward to its advances.

Meanwhile, David Hornyak doesn’t see AI affecting his life. “Well, that’s probably a question to ask [my children and grandchildren]. It’s probably scary in some ways and very helpful. Probably in the field of medicine, it’s going to be a big help, but we’ll see.”

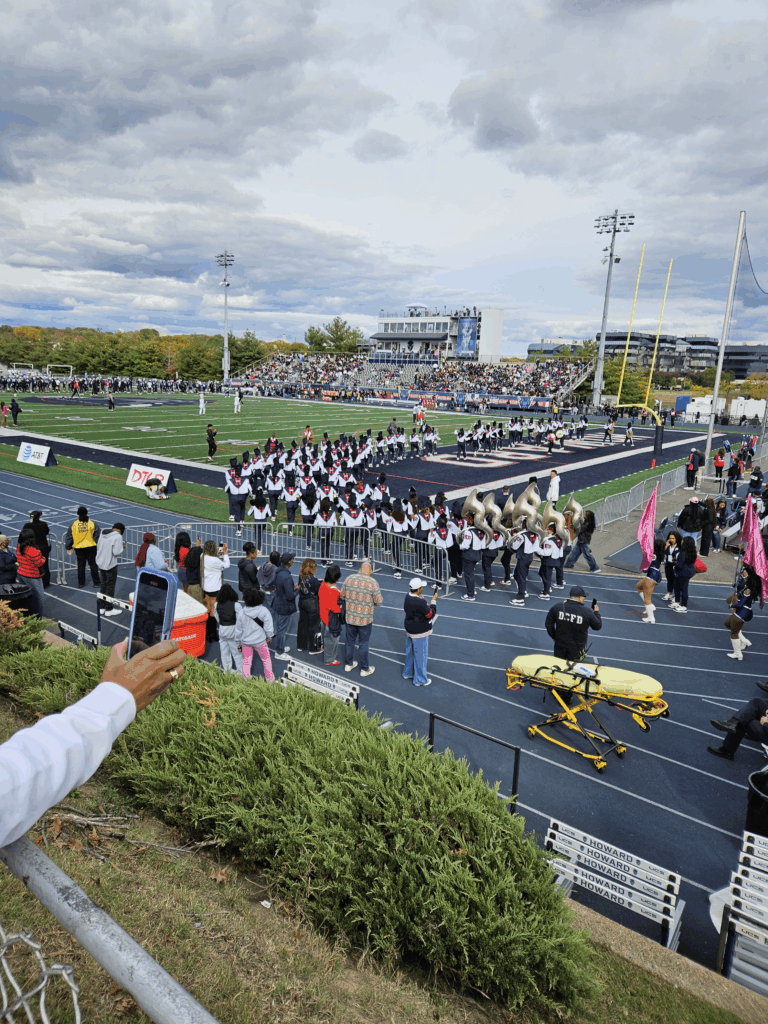

Howard University in Washington, DC (Big City)

By Cece Fadopé

The football game between Howard University and Morgan State University — two well-respected HBCUs — attracted alumni, parents, and friends from near and far on October 25. Ultimately, it was a day for Howard University to shine as fans celebrated its 101st homecoming event, known as “Yardfest” or “Family & Fun Day.” On the way to campus, police and security officers were on every block. Neighbors lined the street, checking out vendors selling their wares — food, jewelry, cultural clothing, and artifacts, effectively closing Georgia Avenue NW, the main road artery of the Shaw Howard University community in Washington, DC.

Never mind the chilly air; many revelers pranced around in revealing costumes. Loud cheers resounded through the Yard — the Marching Band was strutting away after playing, followed by a parade of Greek-letter groups and more cheers from the homecoming cheerleaders. But YB Norris stood away from the festivities, in a corner by the Armour J. Blackburn Student Center building, preoccupied with his phone. He doesn’t tailgate but enjoys watching football.

YB (née Justin) Norris, 24, is an artist from Philadelphia. He came to the Yardfest and game with friends. YB is the moniker for his clothing line and art. He followed the entrepreneur’s path because he could not afford college. He grew up in a single-parent household with his mom, and his parents were unable to help him. Of course, college is valuable, he said. “You learn life skills, social and communication skills too, that I’ve had to learn the hard way, through life, just going through it.” He met good people through “Spark Sessions and community gatherings while playing music,” he said. Norris received marketing training and other skills support from the DELCO Youth Organization in Delaware County in Pennsylvania.

Norris believes diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) is necessary until “there’s a level playing field.” According to him, it is “uncanny how DEI is presented and how the policies work. Look, formerly enslaved Black people built much of this country, a large portion of it.” He continued, “We run our own programs and businesses, we created our own culture, music, fashion, sports, but then people are put in [identity] boxes; it’s just uncanny.”

Asked whether he’s troubled by the spread of artificial intelligence, Norris said he’s become used to it as a gamer and “leverages it as a blueprint for his art and fashion business.” He started learning about AI from video game systems. For him, the only drawback to AI is that “it can warp reality, and we must not let it take our creativity away.”

Meanwhile, Muriel Hatcher, 69, was walking briskly toward where the DJ was playing a favorite tune the revelers sang along to. She also does not tailgate. A Howard alumna from the class of 1978, she attended because homecoming is a special event. Originally from New York City, she resides in Dallas, Texas, where she works as an auditor.

Hatcher has always been happy with her choice of college and subsequent career opportunities. Attending an HBCU, especially Howard University that was founded in 1867 with the motto Veritas et Utilitas, Truth and Service, taught her how to master white America. “It is my responsibility to stay on top of my mindset and attitude about life,” said Hatcher.

In her view, diversity programs are needed but would not be necessary with better policies and practices. “Open clear admissions policy that provides opportunity for everyone” would do more for diverse advancement than any DEI programs. “We won’t need diversity programs if we help our people and open doors for our young people,” said Hatcher.

Hatcher answered a question about the Trump administration’s interference in academia with a question: “What’s the point of being alarmed by what the President is doing or attacking him? You already know he’ll come back to you double, and he has the power.”

Hatcher expressed her ideas about moving forward. “What we need now is strategy and a plan, and in my opinion, that is to vote.” In this regard, African Americans need to be more effective. “Our poor turnout in the last election gave the results we have now. People need to understand the importance of the vote and to be effective about voting at all levels of government.”

Hatcher holds a deep respect for culture as well as for country and disapproves of how “AI is creating mistrust among people. Our people must take it seriously, learn about it, and monitor it carefully, so that means our community must keep up and keep moving at the pace of change,” she said.

In perhaps another sign of the times, a few people approached at the tailgate were wary of sharing their views about these hot-topic concerns.

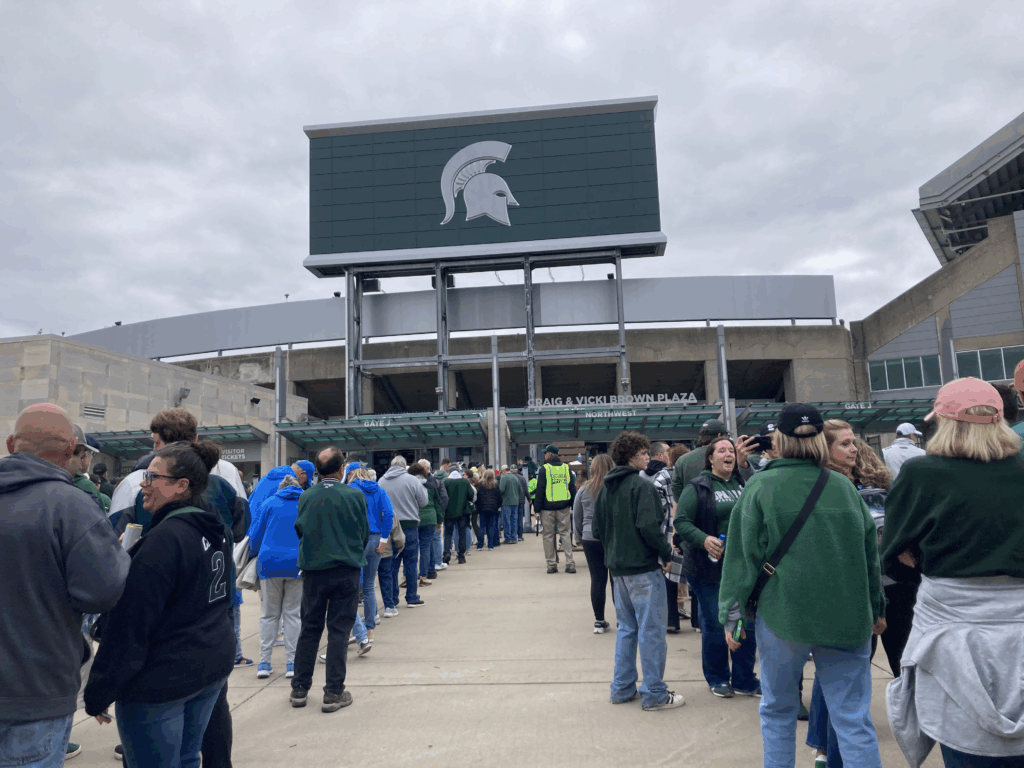

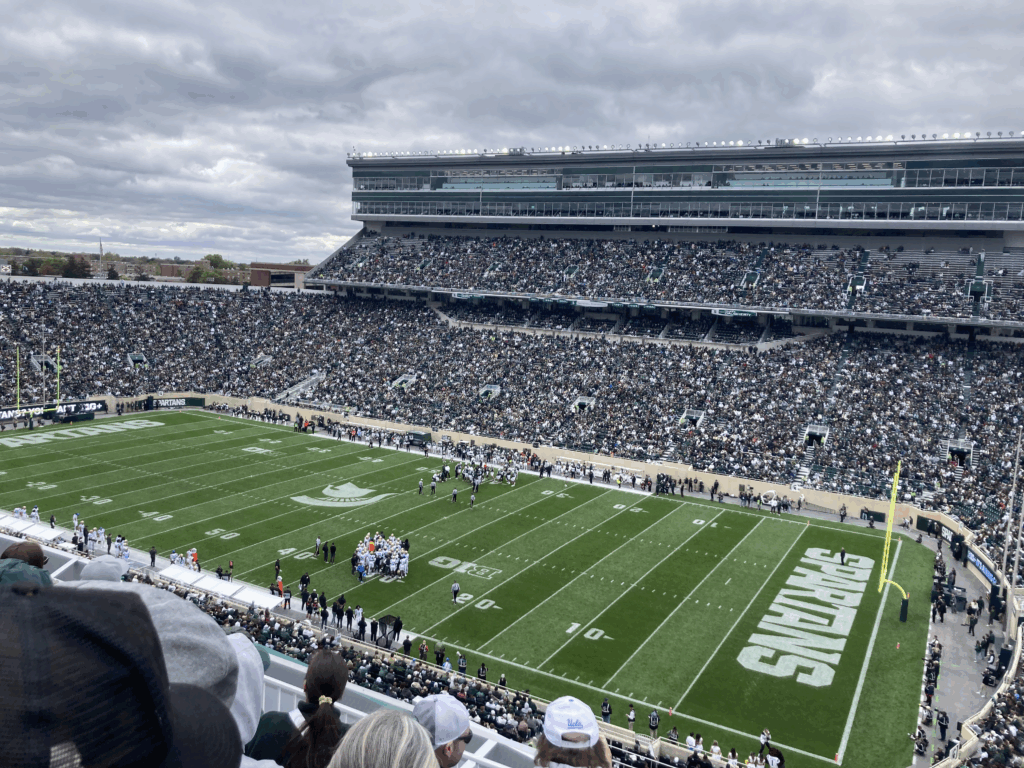

Michigan State University in Ingham County, MI (College Town)

By Theo Scheer

It was a lively scene in East Lansing, Michigan, on October 11, as hundreds gathered on Michigan State University’s campus for the Spartans’ homecoming football game against the UCLA Bruins.

Chants of “go green” and “go white” erupted from tailgaters at random, reverberating through the brisk morning air. A man in a green morph suit weaved through the line to the Spartan Stadium on a bicycle fitted with a massive MSU flag, high-fiving fans.

Many tailgaters came to East Lansing from across the state, and for some — judging by the rare flash of UCLA blue and gold — across the country. Though their backgrounds and political persuasions varied widely, tailgaters were more eager to talk about what brought them together: friendship, their education, and, of course, football.

Merrill Shelter, a carpenter from Lansing, said he was “born into” tailgating. He was raised in Fenton, a small town in Genesee County, a Middle Suburb. His parents started taking him to games when he was five years old. Now, at 50, his teenage son tailgates with him.

Shelter dropped out of MSU in 1994, after his mother told him to pick a major or she’d stop paying for his education. He regrets not enrolling in MSU’s renowned turfgrass program, which he said would have helped him during a stint working in golf course management.

Having been raised to value diversity, Shelter supports college diversity programs and called Trump — who has sought to get rid of them — a “b****.” He doesn’t feel represented by politicians in general, viewing them as power-hungry and “corrupt.”

Others were not so forthcoming about their political views. As old friends and dormmates reunited in the left-leaning college town that morning, for some, politics seemed to be a prickly subject. In fact, many declined an interview as soon as it became clear they’d be asked about current events.

“I’m not going there,” said John Armstrong, a 64-year-old who works in sales, when asked his views on President Trump’s interference in higher education.

Armstrong, who described himself as fiscally conservative and somewhat socially liberal, was tailgating with his fraternity brother, John McKay, a 66-year-old retired sales team manager and self-described libertarian. They’ve been tailgating in East Lansing since the late ’70s, and went to MSU together in the ’80s, where they made lifelong friendships.

Going to college “changed my life,” McKay said. It “tied everything together, gave me a purpose.”

Though they wouldn’t talk about Trump, both agreed that the government should stay out of their lives, and that American presidents generally “have no business” in university operations.

Government involvement is not an abstract issue at Michigan State as MSU’s president made clear in a financial update to the university community on October 22 via email: “As of Oct. 1, 74 federally funded projects at MSU were terminated by the federal government, with a multiyear impact estimated at $104 million. Most were funded by the National Science Foundation, the U.S. Agency for International Development, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Agriculture” and noted “83 positions across the university were lost due to federal funding cuts.”

Two Friends on Higher Ed Issues and AI

Down the street from Armstrong and McKay was Desmond Miller, the policy director for the Michigan Senate Democrats.

The 32-year-old graduated from MSU in 2015 and lives in Flint, which is in Genesee County. He believes college diversity programs are places “where you learn to have respect for people’s differences.” Miller said he doesn’t like Trump’s approach to higher education, saying he appreciates when presidents give colleges more funding and federal support.

Miller was tailgating with Matthew Jones, a friend from MSU who now works for MSU’s College of Communications Arts and Sciences as its associate director of development. Jones is 35 and lives in Williamsburg, which is in the Rural Middle America county of Grand Traverse.

Asked about his hopes and fears around artificial intelligence, Jones said he appreciates its efficiency, but there “needs to be a human element involved” to ensure its accuracy. Miller agreed, saying humans need to catch up to the rapidly advancing technology.

The University of New Mexico in Bernalillo (Big City), Los Alamos (Exurb), McKinley (Native American Land), Taos (Hispanic Center), and Valencia counties, NM (Hispanic Center)

By Sarah Murphy

Author’s note: I did not include specific titles, company names, and last names for Dominic and Orlando, as they’re federal workers, and I wanted to protect their privacy.

Students, alumni, and fans of all ages and backgrounds set up tents in the lots near Louie Lane, The University of New Mexico’s new tailgating hub in Bernalillo County, tuning their radios to the pregame show ahead of the night’s centennial homecoming game. In a state with no major league sports teams, UNM tailgates draw fans from across New Mexico, so it wasn’t surprising that the tailgaters I spoke with weren’t UNM alumni but had still shown up in red shirts to cheer on the Lobos.

Jack McFarland and his wife, Karen, are longtime Gallup, New Mexico, residents and frequent tailgaters who were joined by two friends. The group nominated Jack to speak about education, given his background as a former principal and current school district leader. Jack earned his degrees in marketing and education from both state and private universities in New Mexico. While his education was essential for his career, “I think there are different ways to go about being successful,” Jack said, mentioning how pathway programs prepare students in his district with technical, career-ready skills alongside standard academic courses.

The McFarlands also saw how diversity programs can address socioeconomic opportunity gaps. Working in a school district where the majority of students come from communities that are historically underrepresented in higher education, Jack indicated that diversity programs aren’t an abstract debate so much as giving every student an opportunity to succeed. “I think everybody deserves a chance,” Jack said, as Karen nodded in agreement.

Across the parking lot, Vince, Marcie, Orlando, and Dominic — all members of the Navajo Nation — were enjoying one of their first UNM tailgates. Dominic, 40, and Orlando both earned degrees in Arizona and now work in healthcare near Crownpoint, New Mexico. Dominic and Orlando’s degrees were essential to their jobs, and career advancement will require more. But Dominic, hesitant to begin a new program himself, tells kids to “get in and get out” of college quickly — a caution against taking scholarships for granted amid uncertain federal policies.

Still, the group touted the value of education. Dominic sees college as a chance for students to “build career leverage” and “an understanding of what [they] can offer” to a job. He noted the value of access to university health insurance, which many in communities near Crownpoint don’t have. Marcie and Orlando also spoke of the value of diversity programs in making students “feel comfortable,” especially if they’re new to a community, though Marcie pointed out that these programs may be seen differently depending on where you live.

Coincidentally, both groups of tailgaters hailed from McKinley County, New Mexico, a Native American Land county in the American Communities Project. They had similar perspectives on the federal government’s involvement in higher education, reflecting on long-standing challenges tied to their local communities. Jack and Orlando each mentioned that schools in northwest New Mexico rely on Filipino teachers with J-1 visas to fill critical teaching gaps. Jack sees present-day challenges facing teachers, including shortages, as lingering effects of policies like No Child Left Behind. In both conversations, there seemed to be a sense of worry about how new federal policies might impact local classrooms, where students need steady teachers and reliable scholarships now to prepare for college.

Sentiments around AI were ambivalent. “It scares me not knowing what it’s capable of,” Karen admitted, and others shared her concerns about how AI is evolving faster than our understanding. Dominic and Marcie expressed apprehension about AI’s trustworthiness and potential privacy risks. Despite hesitations, both groups agreed that AI is becoming a critical tool for the U.S. and for students to learn and use responsibly. “We need to use it before we lose it,” Dominic said, referring to the need for the U.S. to keep pace with AI advances and remain globally competitive. His comment echoed Jack’s view that AI is becoming an essential skill for the future: “If you don’t know AI, you won’t be successful.”

Montana State University in Gallatin County, MT (College Town)

By Allison Brennan

November 8th was an abnormally warm fall day in Bozeman, Montana — sunny, brisk, no snow in sight — as the Montana State Bobcat football team prepared to play the Weber State Wildcats. Outside the stadium, people of all backgrounds journeying from across Montana convened to drink beer, play cornhole, and catch up with family and friends. I was there to talk with Montanans and transplants alike about some not-so-celebratory issues: the value and state of higher education in America and the prospects of AI on the horizon.

Change, a constant theme in the West, has borne down on Bozeman in Gallatin County, where the Paramount show “Yellowstone” partly takes place and the pandemic exodus from major cities brought in many newcomers. In more rural parts of the state, this area is pejoratively known as “Boze-angeles” for seeming unlike the “real Montana.” Politically, it deviates from most of the state. Gallatin County, the home of Montana State University, voted for Democrat Kamala Harris by 4 points in 2024. President Trump won the state by 20 points.

Bozeman’s sheer growth has rocked the locals. In the past five years alone, Bozeman’s population jumped 19% to almost 60,000. A cornerstone of the community, Montana State is also a beneficiary of its growth. Like the rest of the Treasure State, the university is not as diverse as other schools of its size in the U.S. — its undergraduate population is 83% white.

Still, I met tailgaters of diverse backgrounds, most of whom said that whatever diversity the university can bring in counts as a positive for rural residents here; who said college has value but is too expensive; and who expressed mixed views about the prospects and the threats of artificial intelligence, often in the same breath.

Assessing College’s Worth

Sherrie Kitto, a 50-year-old mortgage lender, was tailgating with her husband. A mother of five, she said the value of college varied with her kids. Some went to college; some didn’t. She affirmed college’s importance, particularly for the generation of children in middle and high school during the pandemic’s isolation. “I think the value of college is learning to work together, to meet peers, to work as teams, to fine-tune your writing skills and your listening skills and your speaking skills,” she said, adding that the credential itself matters less than the experience. “I don’t know if my degree has helped me get where I am, but I’m proud that I went, and I do think I have a leg up on a lot of people who didn’t.”

Joan Fuller, 59, a health-system imaging director originally from Ohio, brought up the cost of higher education. “College is too ***damn expensive,” she said. “Kids can’t go to school. It’s bull****.” Fuller had paid $96,000 in student loans for her son: “How does a kid pay that on his own? You’re never out of debt.” She contrasted that with her own college era: “One quarter was $400; $1,200 for a year. You could work part-time and pay for college.”

But Fuller still believes college matters. One of her sons thrived in college; one didn’t go and works in a steel mill earning stable wages.

Sipping martinis and canned wine with Fuller was Jenny Runkle, 60, a nurse practitioner originally from Summit County, Colorado. Her path was nonlinear: “I barely graduated high school and immediately became a ski bum,” she said. “At 40, I decided to go to nursing school. At 50, I got my NP degree online.” She said today she owes “$100,000 that I haven’t had to pay yet.” Yet she doesn’t regret going: “Look what I get to do — I get to ease people’s suffering.”

Affordability concerns crossed generations.

Tyler Vaughn, 22, a diesel mechanic from California’s Central Valley, said, “College is a great opportunity for anyone who wants a field that requires it.” However, he wishes he had had the companionship that some of his friends gained from going to college, he added.

But Sam Johnson, a twentysomething blue-collar worker from Butte, Montana, said he feels optimistic about his future in the trades. “The next generation of millionaires will be electricians, plumbers, and anybody working blue-collar jobs.”

Christy Hauk, a 52-year-old mental-health therapist from New Jersey, said college has enormous value and pointed to its lasting imprint on her life. “I went to West Virginia [University] in 1992 not knowing a soul,” she said. “But it was the best four years of my life. My college girls and I are still extremely close.” Hauk grew up in a racially diverse environment, and when she moved to Montana, the stark contrast hit her. “Where I grew up, there was so much diversity. When I moved to Montana, I was like, ‘Where is everybody?’”

On Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) programs

Most attendees interviewed said they favor DEI in university programs, including admissions.

Evan McBride, a 36-year-old college graduate now employed at a compost company, shared a ringing endorsement of the policy, particularly in Montana. “Learning about people who are different from yourself and who come from different backgrounds and different cultures — those are, like, some of the great pleasures in life. Just gaining new knowledge. I mean, I grew up in Montana. We’re a little sheltered here, so we didn’t and we don’t get a lot of diversity. So, when I get the opportunity to meet someone from a different background, and they grew up in a different lifestyle, I like to take advantage of that.” McBride, a native of Helena, went on, “I don’t want to just hang out with people that are exactly like me. That would get boring….”

Cash Kelly, 25, a finance professional from Butte, echoed this sentiment. “I’m a fan of DEI. [Diverse students] didn’t have a leg up in the past, and now to punish them again… it’s a problem.”

But Douglas Johnson, a 53-year-old San Diego native and former Marine who now lives in Montana, had a different and blunt take: “It’s garbage. Don’t ever do it. Equal is equal.”

Getting Candid on AI

One common theme emerged in attendees’ nuanced perspectives of AI: Nobody feels fully in control of what’s next.

“I think, like, workflow stuff — for small businesses, it’s super helpful,” said Kelly, the finance professional. “Just seeing it firsthand, it’s good for small businesses.” Others agreed, especially when AI makes daily tasks faster or more accessible. “I use it for treatment plans,” said Runkle, the nurse practitioner. “When it helps me, I love it.”

But not everyone was as optimistic.

“These things look so real — AI can steal from everybody,” said Hauk, the mental-health therapist. “There are amazing things AI can do in medicine… but there’s no oversight. It can go south fast.”

Patrick Bauerle, a 51-year-old father of five who works in a Darigold milk processing plant, put it bluntly: “I hope it doesn’t turn out as bad as it seems like it’s probably going to.”

And Johnson, the Marine, worries about AI as a tool for political control. “If artificial intelligence is created by people who influence the country in a positive way, it could be good. If not, it could be very, very bad.”

Brigham Young University in Utah County, UT (LDS Enclave)

By Alex Bass

On a mid-October weekend, Provo, Utah, was bustling with foot traffic and tangible energy in the air. Arguably the most covered and heated game of the year was about to take place, the Holy War rivalry game: BYU vs. Utah. The start of the game neared as the sun faded, casting warm light on the towering Wasatch mountain front painted with the red, orange, and yellow colors of fall. It created a beautiful backdrop to BYU’s LaVell Edwards Stadium. A sea of blue fans and occasional red streaks flooded the streets pouring into the stadium. The tailgate scene outside provided a look into the minds of Americans coming together for sport who are separated by ideas around equity, education, and direction for the nation’s future.

The non-student fans offered mixed feelings on the value of a degree. Chris, a Salt Lake City resident holding an advanced degree, said his degree was “worth it,” but acknowledged the value of the trades, conceding that college is not for everyone. (Watch the interview on YouTube.)

Rennie, a native Hawaiian drilling engineer, said he is a “firm believer in the trades,” but acknowledged the essential nature of college for certain professions.

Marla, a grandmother visiting from Oregon, values college for goal-setting and lifelong learning, but questions the affordability — especially outside of BYU, a church-subsidized private college founded in 1875 by Brigham Young, the second president of The Church of Jesus Christ Latter-day Saints. The sting of affordability is acute in “graduate programs,” such as medicine and dentistry that some of her grandchildren currently attend.

All three found value in higher education, but the common threads of affordability and the trades suggest skepticism of college value for the cost of a degree.

The most division among interviewees surfaced in discussion around equity and education. Chris felt like diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) programs were important for “equal representation” and to ensure minority voices are heard. Marla agreed with the idea of equal opportunity with this reservation: “I have a problem with diversity when it excludes some people… it backfires and does the opposite of what it’s supposed to do.” Rennie fell on the other side of the spectrum, framing the issue as merit-based — “the best person gets in… you just gotta be the best.” He was displeased with DEI overall.

The same tension carried over to the role of government. Chris and Marla agreed that higher education should remain independent. Chris highlighted a need for a “distinction” between academia and government. Marla emphasized the importance of a school having power to choose their own curriculum, especially with religion courses. Rennie disagreed, saying that higher education has leaned “way too hard” to one side justifying external corrective action toward a neutral focus based on the country’s founding principles.

Finally, all interviewees expressed hope for artificial intelligence as a powerful resource yet feared potential and invasive uses. Rennie highlighted a fear of AI having access and being trained on personal data which felt “invasive.” Marla expressed concerns specifically in hindering users’ ability to think. Ultimately, they see its utility yet fear overreach violating privacy and curbing critical thought.

University of California–Los Angeles in Los Angeles County, CA (Big City)

By Jenna Modica

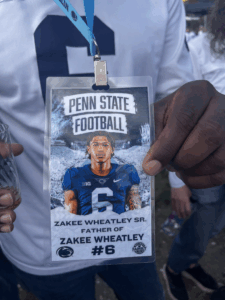

On a surprisingly chilly 64-degree October day in LA, football fans and families lined the Rose Bowl lot eager to see the UCLA Bruins play the Penn State Nittany Lions. That day, the cost of parking was $44, higher than the normal rate of $36, because Penn State is a premier opponent. The grassy fields were chock full of blue and white tents — blue for UCLA, white for Penn State. In sight, too, were sponsor booths, like Fox, a tequila company, and Insider Accident Lawyers. Following Insider’s Instagram gave fans a chance to win a cute plastic reusable tote bag!

While the crowd waited for the football players to arrive, security lined the blue carpet. Many security guards greeted fans with a handshake, name introduction, and a welcome to the Rose Bowl. Both teams browsed the UCLA merch shop’s many tables. Among the packs of UCLA fans of all ages, ethnicities, and races, Penn State was well represented in a sea of white.

Mingling almost by themselves, a group wondered aloud, “Where is Penn State? Oh! Pennsylvania? Geez, so it took five hours to get here? I’ve never been to the East Coast.” The sea of white shirts caught my attention, too, and I struck up a conversation with Zakee Wheatley Sr., whose son, Zakee Wheatley, is a senior and a safety on Penn State’s team. Wheatley Sr., who hails from Maryland and now tailgates at every Penn State football game, came here with his wife and some friends. He oozed excitement about his son’s recruitment as he affirmed the importance of going to college. Diversity programs should have a greater presence at colleges and universities, he said, to give more people opportunities to succeed.

Like many colleges this past year, UCLA has been in the crosshairs of the Trump administration. In August, UCLA said the administration suspended more than $500 million in federal grant funding “over allegations of civil rights violations related to antisemitism and affirmative action.” A federal judge has since ordered restoring $500 million in federal funding. As Wheatley Sr. saw it, President Trump “should be focused on bigger things” than the operations of colleges and universities. “Put my name next to that.”

Later, I met Ron Takasugi, 69, a retired LA resident who’s attending every UCLA home football game this season. He’s been a season ticket holder for the past 36 years. That Saturday, family and friends filled his tent and contributed to a potluck breakfast with a Mexican flair. In a regular ritual, a head chef chooses the food theme for each game, he said.

Takasugi, whose tent was full of UCLA alumni, effusively spoke of how his UCLA experience helped him get started in his accounting career.

Listen as Ron Takasugi describes how a UCLA degree gave him a leg up in the hiring process — more than once.

UCLA sports have helped Takasugi connect in business throughout his career. “I’ve talked to friends of mine who are USC grads, Trojans, and from a business perspective, it’s very easy for me to walk into a room dealing with a UCLA person but also with SC because you have this common rivalry already, and this carries over to the business side, but it’s a friendly rivalry. That’s what UCLA does. It opens doors for you. So many connections.”

Takasugi celebrated UCLA’s vibrant diversity and the way the university continues to welcome students of different backgrounds in the newest class. He doubted whether the Trump administration understands “the lay of the land” when getting involved in the operations of colleges like UCLA. “I got to believe in general, college environments are more liberal than what the current administration likes, and that’s why [Trump] naturally is trying to squelch things. But the education process has been this way for many years, and there are many Republicans and many Democrats that all attend, whether an Ivy League school, any of the private schools here, and … UCLA, Michigan, Virginia, Texas … all the big public schools.”

On the issue of artificial intelligence, his views are not fully formed. “My son works for Google. So, I get the AI scoop. I’m sure AI is affecting my life today; I just don’t know it. And I’m not smart enough to know everything that goes on with AI. I drive a Tesla, and there must be AI in that thing because it self-drives.”

What Takasugi knows is AI is good for doing research. “We used to have these rooms with giant libraries; now you pull out your phone or your desktop. Find this case on ChatGPT,” he said.

Ari Pinkus is senior editor/writer/researcher and project manager at the American Communities Project.

Ari Pinkus is senior editor/writer/researcher and project manager at the American Communities Project.

Cece Fadopé is a public information specialist in Washington, DC. She was previously a producer for Pacifica Radio WPFW, NPR News, VOA Africa Service, a media manager for Internews, and a fellow of the International Center for Journalists.

Theo Scheer is a freelance reporter at Michigan State University, where he studies journalism, anthropology, and the digital humanities. He was previously a senior reporter for the student newspaper, The State News, and an intern at The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Theo Scheer is a freelance reporter at Michigan State University, where he studies journalism, anthropology, and the digital humanities. He was previously a senior reporter for the student newspaper, The State News, and an intern at The Chronicle of Higher Education.

Sarah Murphy is a recent Albuquerque, New Mexico, transplant who enjoys writing about the intersection of people, place, and community.

Allison Brennan is an Emmy-nominated freelance journalist and producer based in Livingston, Montana. Co-founder of 64 and Sunny Studios, Brennan worked for CNN and CBS News for a decade before she went out on her own. She now works with independent journalists and creators on their new endeavors and walks her four dogs along the Yellowstone River in her free time.

Allison Brennan is an Emmy-nominated freelance journalist and producer based in Livingston, Montana. Co-founder of 64 and Sunny Studios, Brennan worked for CNN and CBS News for a decade before she went out on her own. She now works with independent journalists and creators on their new endeavors and walks her four dogs along the Yellowstone River in her free time.

Alex Bass is a data scientist and founder of Mormon Metrics, an influential blog that analyzes Mormon demographics and culture. Leveraging his political polling and data background, he consults for corporate and political clients and helps them turn messy data into actionable insights.

Alex Bass is a data scientist and founder of Mormon Metrics, an influential blog that analyzes Mormon demographics and culture. Leveraging his political polling and data background, he consults for corporate and political clients and helps them turn messy data into actionable insights.

Jenna Modica is a production assistant and freelance writer in Los Angeles with experience across indie films and large-scale production.

Jenna Modica is a production assistant and freelance writer in Los Angeles with experience across indie films and large-scale production.

Marc Maxmeister, Senior Data Scientist at GivingTuesday, helps organize and convert the world’s generosity data into meaningful insights into how giving works, and what organizations can do to improve the lives of people served. He brings context from mixed methods field research in Africa, rigor from his Ph.D. work as a molecular neuroscientist, and engineering from past AI-driven startups and nonprofits.

Marc Maxmeister, Senior Data Scientist at GivingTuesday, helps organize and convert the world’s generosity data into meaningful insights into how giving works, and what organizations can do to improve the lives of people served. He brings context from mixed methods field research in Africa, rigor from his Ph.D. work as a molecular neuroscientist, and engineering from past AI-driven startups and nonprofits.