Fulton County, Arkansas: Working Class Country

At the foothills of the Ozark Mountains where the hills run on for miles sits Fulton County, Arkansas, a Working Class Country community of 12,055, founded in 1842. And on the Arkansas-Missouri line, in the town of Mammoth Spring (pop. 990), one of the world’s largest springs flows and the Civil War’s vestige still echoes. The Old Soldiers, Sailors, Marines, and Air Force Reunion has gathered here each summer going on 126 years, starting as a Reunion of the Blue and the Gray to heal the war’s divisions. “Fulton County men fought on both sides in the Civil War…” begins a marker at the Mammoth Spring State Park.

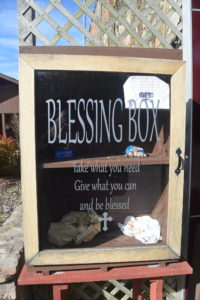

It’s true that many families can trace their roots back generations, and a comforting sense of home envelops today’s residents from bankers to educators. Fulton County boasts solid schools in the state with dedicated, well-trained teachers; its 20-plus churches stand as a rock for the community. A Christian mindset, including a deep faith and caring for your fellow man, shines through in conversations, even in a sidewalk “blessing box” display to “Take what you need” and “Give what you can.”

It’s true that many families can trace their roots back generations, and a comforting sense of home envelops today’s residents from bankers to educators. Fulton County boasts solid schools in the state with dedicated, well-trained teachers; its 20-plus churches stand as a rock for the community. A Christian mindset, including a deep faith and caring for your fellow man, shines through in conversations, even in a sidewalk “blessing box” display to “Take what you need” and “Give what you can.”

At the same time, residents are clear-eyed and candid about their many challenges: infrastructure gaps, severe economic hardship, drug addiction, apathy, and perhaps most urgently, a youth brain drain, which has been emptying the county of the talent needed to help turn around these challenges. Fulton’s population has declined 1.5% since the 2010 census.

While the economic and social barriers to growth are high, the conditions are ripening for green shoots to pierce pockets. Several community leaders are rolling up their sleeves to bring renewal in the forms of broadband Internet access; water expansion; a tri-county grant for training in the retail, hospitality, and recreation fields; an innovation hub; and financial literacy. Fulton’s future, it seems, is very much a work in progress local residents are building day by day.

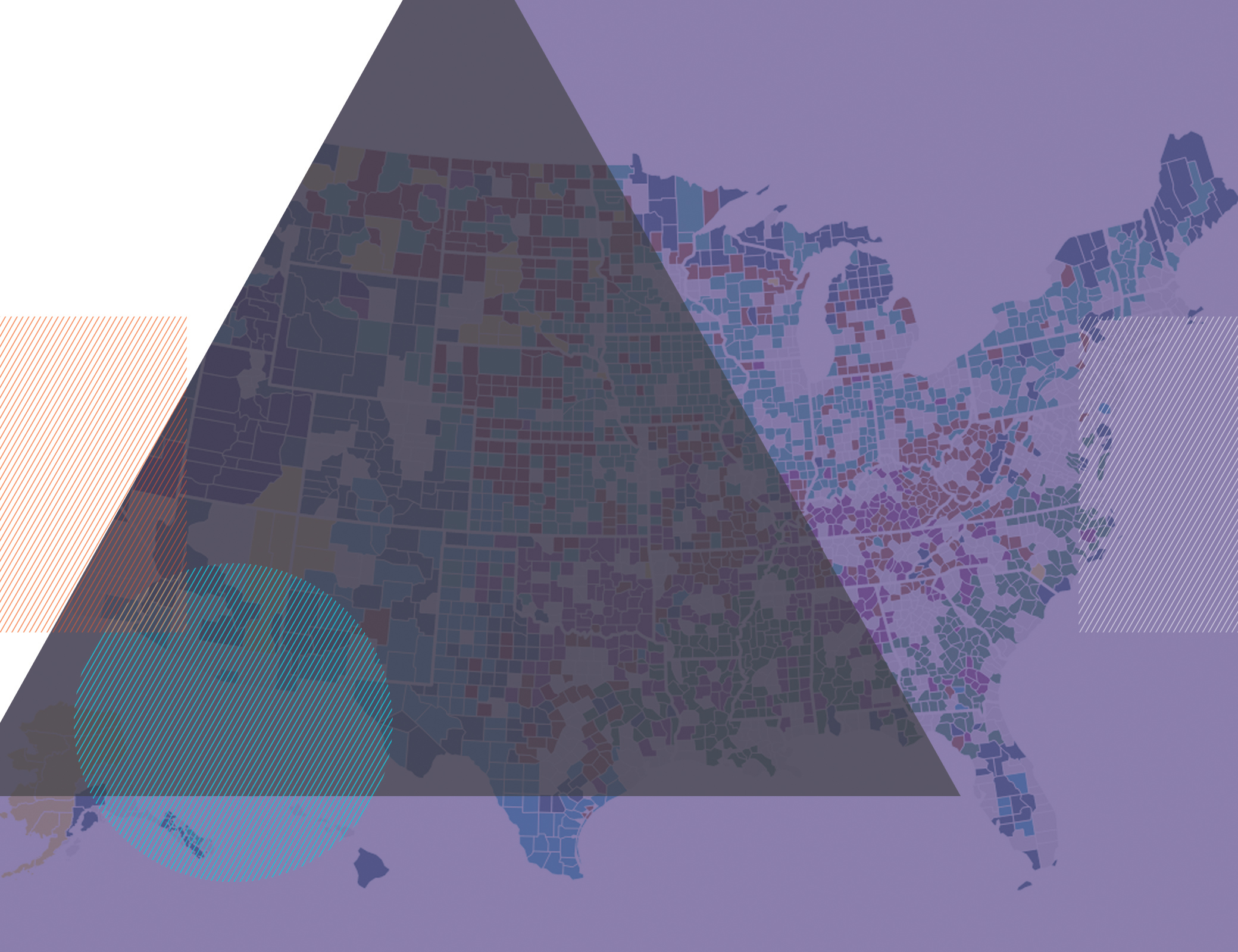

Fulton County Index

Fulton County Within Working Class Country and Rural America

Building an Infrastructure

Moving to Revitalize a Depressed Economic Landscape

A Pilot for Economic Development

Reimagining Cherokee Village

Meeting Individual and Community Health Needs

Institutions Nurturing Youth

Fulton County Within Working Class Country and Rural America

Working Class County is among the least diverse community types in rural America, with a population that’s 94% non-Hispanic white. Fulton County follows this pattern: 95% identify as non-Hispanic white; 1.3% as Hispanic; and less than 1% as African American, Native American, or Asian.

Socioeconomic factors convey Fulton’s hardships. The median household income is $35,700, with 29% of children in poverty, and 30% living in single-parent homes. Compare this to the household income medians of $43,800 in Working Class Country and $46,600 in rural America. The child poverty rate is 24% in Working Class Country and 22% in rural America. A bright spot: The high school graduation rate is 98%; it’s 92% in Working Class Country and 90% in rural America.

Health outcomes and additional factors show a county in great distress, according to the 2019 County Health Rankings:

-

-

- The premature death rate of 12,300 exceeds Working Class Country’s rate of 9,400 and is considerably higher than the rural America median of 8,641. Lack of health-care access, unhealthy behaviors, and depopulation likely contribute to this high number.

-

-

-

- Teen births stand at 44 per 1,000 females ages 15 to 19 — a much higher rate than the 36 median in Working Class Country and the 34 median for rural America.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Preventable hospital stays are 6,972, while Working Class Country’s and rural America’s rates are much beneath that at 4,949 and 4,732, respectively.

- Access to dentists is very poor with a ratio of 6,030:1. This compares with 3,265: 1 for Working Class Country and 2,802:1 for rural America.

-

-

-

- The food environment index is weak at 6.6; for Working Class Country, it’s 7.7 and for rural America, it’s 7.6.

-

-

-

-

- Overall, 22% of Fulton residents say they are in poor or fair health, compared with 18% in Working Class Country and 17% in rural America.

-

Building an Infrastructure

Broadband

“By supporting this measure we help … improve rural living standards, equalize farm and city cultural advantages, and strike a great blow for economic betterment throughout the land.” It was April 1936 when Rep. Thomas Fletcher (D) of Ohio spoke these words in the U.S. Congress about the Rural Electrification Act, which became law a month later. After which time, rural residents came together and organized electric cooperatives to connect their regions to electricity; more than 900 such cooperatives exist today. One is North Arkansas Electric Cooperative, based in Fulton County, employing 125 people.

Now many electric cooperatives, including North Arkansas Electric, have expanded their focus to provide broadband Internet for the same reasons. “We’re at a point with broadband we were at years ago with electricity. For the folks at the communications companies, the cable companies, their business model does not fit rural America….That is exactly the reason my coop is investing $130 million for fiber-delivered high-speed broadband,” says Mel Coleman, CEO of the North Arkansas Electric Cooperative, which serves Fulton, Baxter, Sharp, Izard, and parts of Lawrence and Stone counties, counting 31,000 members. A $4 million pilot project in the region was completed last year. North Arkansas Electric has been partnering with others, including Como Electric Cooperative in Missouri, which has been in broadband for more than six years.

Now many electric cooperatives, including North Arkansas Electric, have expanded their focus to provide broadband Internet for the same reasons. “We’re at a point with broadband we were at years ago with electricity. For the folks at the communications companies, the cable companies, their business model does not fit rural America….That is exactly the reason my coop is investing $130 million for fiber-delivered high-speed broadband,” says Mel Coleman, CEO of the North Arkansas Electric Cooperative, which serves Fulton, Baxter, Sharp, Izard, and parts of Lawrence and Stone counties, counting 31,000 members. A $4 million pilot project in the region was completed last year. North Arkansas Electric has been partnering with others, including Como Electric Cooperative in Missouri, which has been in broadband for more than six years.

Fulton County’s broadband access rate stands at 60%, lower than Working Class Country’s 66%. In context, Arkansas is the 49th least connected state, with just 71% percent of households holding a broadband Internet subscription, according to the 2016 American Community Survey. The U.S. average stands at 81%.

In Coleman’s cooperative service area, the hurdles are sizable. One is population density, which requires one mile of line for every seven homes. In a city, a mile of line might reach hundreds of homes and businesses. The cooperative has received $22.8 million from the Federal Communications Commission for this project. “We still have another $100 million that we have to fund,” Coleman says. Notwithstanding the challenges, the cooperative expects to deliver fiber-optic broadband to every home in its territory in the next five years, he says.

Basic broadband Internet service, at 100 megabits per second, runs $49.95 a month, Coleman noted. Residential telephone service runs $39.95 a month. Because some rural areas don’t have cellphone coverage, “VoIP is about the only choice they have,” he says. (A local phone company would provide landline service.) Many residents purchase a package of Internet, TV, and phone service.

Coleman envisions broadband’s comprehensive benefits. “I don’t care if you’re looking at education, health care, business development, industrial development, or just a child doing homework at night, broadband is the single most important element in the development of quality of life in rural America,” he says.

Water

To fulfill another area of need, the Fulton County Water Authority has embarked on a new phase to extend water to its more rural areas north and west — slated to reach more than 1,200 customers, says the Water Authority’s Manager Darrell Zimmer. “We’re about a third of the way” toward covering the county, he says.

The biggest obstacle is funding; they will seek low-interest loans from the USDA and grant funding from the Arkansas Economic Development Commission, Zimmer says. Another challenge is the topography — running into rock while trying to install a water main.

Sometimes he encounters residents who are hesitant to move off well water, and he talks with them to understand why and explain the benefits. He finds that some feel they draw good drinking water; others express concern about chemicals. Many come around because they want the insurance and generator backup of the county’s water system, recalling an ice storm in 2009 when they were without electricity for two weeks. “When they see the actual work going on, they want to get on board; sometimes it’s a little more expensive to do that than it is to sign up ahead of time,” Zimmer says.

Highway

Fulton County is situated about two and a half hours from Little Rock, Arkansas, and two and a half hours from Springfield, Missouri — two regional economic hubs. In the past several years, some passing lanes were added on Fulton’s main highway, 62-412, otherwise a hilly two-lane corridor in the national highway system, running through the county seat of Salem (pop. 1,608).

Expanding to four lanes could boost economic development opportunities and reduce local transportation costs. “When you talk to businesses trying to move here, there’s always the issue of trying to get their goods in and out, and there’s always an issue along that route. They’re driving all the way up into Missouri and coming back down,” says Zimmer, who’s also on the North Arkansas East/West Corridor Association board.

The association keeps the state’s studies, has held public meetings, and is seeking federal funding. “We’re focusing on the dangerous areas through the crash loans of the highway department because if there’s a safety issue, they’re more likely to fund that, and it solves two things at once,” he says. Three danger areas have been identified in the western part of Fulton.

Zimmer is cautiously sanguine about the highway’s future. “As far as complete, it probably won’t happen in my lifetime, but we’re making progress,” he says.

Moving to Revitalize a Depressed Economic Landscape

Residents remember Salem’s square bustling with mom-and-pops in the 1980s, particularly on Saturdays. A significant economic loss came when the Tri-County Shirt Factory closed in 2001, and 138 employees lost their jobs. Today, a few shops and one family diner, Swingles, surround the square where the red-brick Fulton County Courthouse stands; a Dollar General is close by on South Main Street.

An eclectic mix of private and public events takes place down the road in Salem at the Fulton County Fairgrounds. The county fair’s theme this year was “Celebrate 100 Years of Fulton County’s Best.” Recently, the Salem Civic Center on-site held a dance recital and a Fulton County Hospital Foundation gospel concert.

Just as often residents harken back to Walmart wanting to build a store in Salem in the late ’60s–early ’70s. The story goes that after the town fathers fought the effort, with concern for local businesses, Sam Walton, who in 1962 opened the first Walmart in Rogers, Arkansas, said there would never be a Walmart in Salem. “If we only had a Walmart…” has become a refrain here.

Lifelong county resident and Salem Chamber of Commerce President Zach Branscum says everyone from state to local residents recounts this part of Fulton’s past. “I hate that story. We can’t focus on things that happened in the ’60s. We’ve got to be more progressive; we’ve got to start somewhere,” he says.

He sees younger people as the linchpin to revival. “People that had money and started these businesses were mostly all from here. That’s what they did their whole life.…That’s why we’ve got to have people that want to come back here and start those entrepreneurial type [businesses]. Because the people that have always been here want to see it like it used to be.”

That doesn’t mean they dislike modern business strategies. Seizing on a national trend, the Chamber started promoting through Facebook “Food Truck Fridays,” in which a few trucks from within and beyond the county set up in downtown Salem about once a month. Branscum hopes the initiative will entice people to visit local businesses and return, he says. The Chamber is also sharing via Facebook “small town spotlights” of businesses to highlight their offerings and help them recruit employees. One was Progressive Eye Center of Salem that sought an optometrist not long ago.

Chamber representatives are under no illusions about retaining young people in Fulton, but take heart in recent education and workforce trends. “Most kids want to go off to college, and they don’t want to come back here because they don’t see any opportunity here…. The trades are coming back. They can start those while they’re in high school,” says Michele Tomlinson, a board member on the Salem Chamber of Commerce. It’s helping keep some people here, she adds.

Branscum, a health-care professional, suggests one way to jump-start more ideas: “We’re all volunteers at the Chamber. It would be helpful to have somebody who would spend their time dedicated to economic development,” he says, noting that neighboring areas pay staff to work in this area.

Other community leaders are focused on improving the local economy as well. “Everybody’s hungry for jobs,” says Salem Mayor Daniel Busch, who also serves on the Chamber of Commerce. As a small community, Salem relies heavily on tax revenues, and its sales tax is about $25,000 a month, 1% of which goes to infrastructure, police, fire, and industrial development, Busch says.

Elected mayor more than four years ago, Busch is a lifelong resident of Fulton who graduated from Mammoth Spring High School in 1999. He describes agriculture — particularly beef and recently poultry — as the main industry in the tri-county region, encompassing Fulton, Sharp, and Izard counties. The mayors and county judges (a county’s chief executive officer) have realized that developing a sustainable workforce requires a regional approach, Busch says. The three county judges, for instance, have been meeting over the past year to discuss what business prospects could come to these parts.

Besides the narrow roadways, a deficiency is that Salem has no natural gas — only propane and electric, Busch says. With the expectation of broadband Internet, there’s a thought the community could begin to attract millennials working online.

A Pilot for Economic Development

A new economic hope stems from the selection of Fulton, Sharp, and Izard counties to participate in a multi-state pilot program, aimed at developing the counties’ retail, hospitality, and recreation industries. The pilot is part of a $2.7 million grant from the Walmart Foundation to the Southern Rural Development Center. Other states involved are Oklahoma and Kentucky.

Launched in January, the Create Bridges project is being run through the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture Community and Economic Development. It held its first retail academy in Salem in the spring. “The retail academy went very well for us. We had around 40 participants and really good dialogue,” says Stacey McCullough, assistant director of community and economic development. In early May, they began conducting interviews with business owners/managers and surveys of workers in retail, accommodations, tourism, and entertainment fields.

“Create Bridges builds upon Stronger Economies Together (SET), a collaborative effort across 32 states led by the Southern Rural Development Center that helps rural counties work together to develop and implement an economic development plan for their multi-county region,” according to Talk Business & Politics, a news site that covers business, politics, and culture in Arkansas.

The project runs right along with Busch’s mission to leave Salem better than he found it. Busch was approached by Mayor Gary Clayton, who led Salem for more than 35 years, to run for this seat. “He paved the city streets and built up the infrastructure. So I want to build on what he left, and then [let] whoever is after me continue building. We don’t need to sit stagnant and go backward,” Busch says.

Reimagining Cherokee Village

About a half-hour southeast of Salem, straddling Fulton and Sharp counties, is the community of Cherokee Village, complete with directional signs and a town center. The vision of Arkansas native John Cooper, it was the first planned recreational community in the state and one of the first of its kind in the U.S. Amenities include seven lakes, two 18-hole golf courses, parks, recreation centers, and swimming pools.

In the 1950s and ’60s, people were recruited to the Village; property owners have hailed from across America and abroad. For many years, Cherokee Village represented a successful graduated retirement model: It attracted young couples in their 30s with kids who made it their getaway, then when their kids left the nest, they returned to settle in the community they loved. In the ’80s, civic engagement was robust.

As retirees passed away or moved to where their children lived, marketing efforts diminished. “There’s this natural cycle here. Problem is, there was no one cycling behind with the same kind of civic minded” mentality, says Jonathan Rhodes, community developer of Cherokee Village who grew up here, then lived in Washington, D.C., Rome, and Sudan. “We’ve got these wonderful assets that are not easily replicated… we have to recreate ourselves.”

This begins with jobs. “The backbone of our community here is tourism and small service business,” Rhodes says. “We’ve got to make sure that we are supporting small business. And we’ve got to create platforms for anyone who’s got an entrepreneurial passion or an idea, or home-based business, or job dependent on technology.”

The new vision of being a small business incubator is starting to come to life in the region’s new Spring River Innovation Hub at Cherokee Village. Part of the town center has become a co-working space, providing high-speed Internet, mentoring, community events, and professional development. The hub was made possible with $20,000 from the Delta Regional Authority and additional support from FNBC Bank. Graycen Bigger, director of placemaking for Cherokee Village, is also the hub’s executive director.

A native Arkansan, Bigger brought her artistic sensibility here after earning a master’s degree in art business from Sotheby’s Institute of Art in New York. “I was very interested in how art impacted communities,” she says. In mid-March, Cherokee Village hosted Arkansas Arts Center’s Artmobile, giving local schools and community groups access to the art show “Who, What, Wear,” focusing on the relationship between art and fashion.

In the renewal of this place, Rhodes and Bigger express the penultimate goal of creating a sustainable community that can continue well into the future.

Meeting Individual and Community Health Needs

For the Fulton County Health Department, drug use, particularly meth, is top of mind. A sales tax increase went into effect April 1 to help the sheriff’s office contend with the problem. The health department team has also earmarked the major health concerns cited in the County Health Rankings: smoking, obesity, lack of dentists, preventable hospital stays, and child poverty. Also on their radar is teen pregnancy, and Health Department Administrator/RN Wanda Koelling confidentially counsels young people to prevent STDs and pregnancy, she says.

One strength of the health department is giving immunizations. Where there’s room for improvement day to day: Having a nurse practitioner who can attend to general health, not only family planning, Koelling says.

A significant challenge on health-care access is similar to many rural areas: Fulton residents must travel 45 minutes to an hour to a major hospital in Mountain Home or Batesville. While Fulton County Hospital has long been a fixture in Salem, it hasn’t provided surgery or obstetric services in many years. However, physicians are on call all the time in what is now a critical access hospital with 25 beds.

Meanwhile, Arkansas’s Medicaid work requirement, which was blocked by a federal judge in late March, has not had a big impact here, according to Koelling. More than 18,000 people in the state had lost coverage after it was implemented in June 2018.

Institutions Nurturing Youth

Schools

Of Fulton County’s three school districts — Salem, Mammoth Spring, and Viola — Salem is the largest and most recognized. Salem Elementary receives an A score and Salem High School a B, according to Niche’s 2019 Best Public High Schools, which draws on academic and student life data from the U.S. Department of Education, test scores, and college data. Mammoth Spring Elementary scores a B+ and Mammoth Spring High School a B; Viola’s elementary school obtains a B+, its high school a C+.

Salem School District focuses on academic success much more than sports, says Wayne Guiltner, who is finishing his third year as superintendent and was previously high school principal for 12 years. ACT scores are above the national average. “With 65% of students on free and reduced lunch in the school, most studies would show we should not be doing that well,” he says.

Guiltner, who grew up here, offers some reasons for bucking these trends. “There is pressure on the school; a lot of that comes from parents wanting their kids to do better than they did.” Moreover, Salem’s teachers continue to obtain 60 hours of professional development each school year, compared with the 36 hours required by the state, Guiltner says.

With a graduating class ranging from 60 to 75 students, the district focuses on preparing students for career paths afterward. In addition to Advanced Placement courses, students have access to community college classes while in high school. “You can get an associate’s degree here, and we pay for the majority of it,” Guiltner says. The district also accommodates students’ interest in the trades, including welding.

Devoted educators, like Algebra teacher Ted Kerley, are role models for students. Born and raised in Salem, Kerley lives on his family’s farm, in the family since 1942. “I have 17 former students working with me now; education is a big deal to us,” he says. A major change he’s noticed since he started 24 years ago: Many more students come from one-parent homes. Teaching life skills is his forte. “I tell kids, I care about you as a student, as a person, an athlete, but I also care about your soul,” he says, careful to add that he does not discuss religion with them.

Kerley was in college around 1992 when Salem High’s longtime Algebra teacher asked Kerley to take his place. Kerley studied day and night to ready himself for the position. “Turns out I had a higher GPA in college than in high school because my work ethic and study habits tripled,” he says.

Church

Salem First Baptist Church’s Pastor John Hodges is also a Fulton County native. He graduated from Salem High School in 1980, then headed off to the Air Force, college, and graduate school. After returning in 1996, he noticed “more of a sense of economic desperation, and that was sad to me,” he says.

The economic and social decline only deepened in the passing years. Hodges remembers arranging a summer job for his son here after his first year in college in 2002. On the phone one day his son said he wasn’t coming home and planned to work at a children’s camp. “All my friends are using drugs,” he told Hodges. As Hodges ticked off names in disbelief, his son confirmed their drug use. In one case, a father introduced his son to meth. Today, the pastor’s son lives in Austin, Texas.

Pastor John Hodges addresses Fulton County’s divides, its stabilizing forces, and the work of serving the needy but not fostering dependency.

As Hodges works to better the community, he pays special attention to young people. His argument: “Do you want to be a recipient, or do you want to be contributor? By being a contributor, you have the possibility to move up, better your life, and better the community.” Because a lot of kids have grown up in homes where they don’t see a work ethic, Hodges teaches them life lessons as well as the Bible. For example, high schoolers and young couples learn how to manage money through Dave Ramsey’s personal finance education. Some have used the saving tips to pay off debts and take vacations, Hodges says.

He’s seen a few young professionals move into or return to Fulton, including his secretary’s husband, a banker. As Hodges puts it, “It’s good to see because they really are trying to make change in the community. But we just need more.”