On a Mission to Stop Youth Suicide in Philadelphia

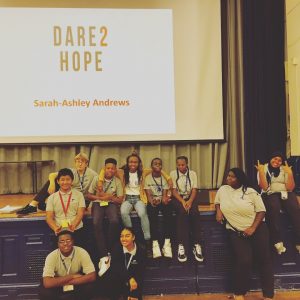

Sarah-Ashley Andrews was 25 when she tragically lost her dear friend to suicide nine years ago. Ever since, she’s been working to give young people the tools to lead healthier lives. In 2012, Andrews founded the nonprofit Dare 2 Hope in Philadelphia, and continues to run the organization today. Its mission is to conquer suicide in youth and young adults, ages 8 to 24.

Suicide, particularly among youth, is an acute challenge all over America, drawing heightened attention in the pandemic. In Philadelphia County, the overall suicide rate is 10 per 100,000 people. For Big Cities, the suicide rate is 11.4 per 100,000. Nationally, the rate stands at 14.3, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s data from 2015-2019. (Philadelphia County’s numbers aren’t available by age.)

I caught up with Andrews for a wide-ranging interview, addressing the stigma around suicide, Dare 2 Hope's approach with youth, adapting to the pandemic, and what gives her hope. Our interview has been edited and condensed below. Listen to the full 19-minute interview here: Sarah-Ashley Andrews Interview

Why Andrews Started Her Work

Back in 2012, I lost a friend to suicide; he died by suicide. We were 25 years old, and it took us all by surprise. We didn't know he was even suffering from any kind of mental illness or suffering with suicidal thoughts. So from that, I wanted to create something where I could educate people. I just wanted to make people aware of what was going on with people's mental health, especially in the Black community.

Using Education and Life Experience as Guiding Lights

When I first went to college, I was a mass communications major. I wasn't even thinking about mental health or anything like that. Once [my friend] passed, I changed my focus to human services. I got my undergrad degree in biblical studies and human services. And then I realized that I wanted to help people in a larger capacity. I went back to get my master's in counseling, psychology. Now I just passed my national counselor examination and am on track to get my license to be a licensed psychotherapist.

So it really has shaped my work; it just allows me to be more knowledgeable. When I first started Dare 2 Hope, I would bring my friend, who had her master's in counseling already, as backup.

Dare 2 Hope’s Open Approach

What makes it unique is that I can be very relatable. I'm small, 5”1’ and like 108 pounds. So I can relate when we go into schools. A lot of schools we go to in the urban community; I grew up in North Philadelphia, which is an urban neighborhood in Philadelphia.

And my approach is to be as real as I can, to be as transparent as I can, with the students, with the teachers, with the staff, because that's how we have real conversations, when we make it a safe place to have unrestricted conversations. And when I'm transparent enough about the stuff that I went through, it makes it easier for people to open up and share what they've been going through.

How the Organization Adapted to the Pandemic

Prior to Covid and stay-at-home orders, we would actually go into schools. We had an opportunity to get face to face with the students, have assemblies, have our workshops that would last for six weeks. So we got to really get to know the students we work with.

When the pandemic hit, of course, all that stopped because school went virtual. But then we had to redirect our program. How could we still reach these children, and not be able to actually see them? So we created a Safe Saturdays program, where we host a virtual platform on Saturdays. Kids can log in and get the same six-week program they would get in their school.

During the pandemic, I also created a podcast, where each week I can talk about mental wellness. So that's something else that I pivoted on, and it created another outlet for us to get the word out about mental wellness.

How People of Different Ages Respond

The older the audience, the harder it is to break the stigma. Younger kids will always talk when you build trust with them. But the older we get, there's more of a fight. So a lot of what we talk about is total mental wellness: healthy eating, exercising, but then a bigger component of that is therapy. And within the Black community, it’s still kind of looked down upon. We can convince teens to live well, but when they get older, the resistance is still here.

Understanding the Stigma Around Suicide

There's so many factors that are behind [the stigma]. One of the factors I have been seeing more is the religious risk factor. And people don't always look at religion as a risk factor. But you got to realize that a lot of times people feel like they are forsaking their higher power by going to seek help for their mental wellness, or people feel like [they’ll] pray about it and leave it alone.

Or there is a stigma attached to it from religious leaders, [who are] telling people, “Listen, you don't need it; therapy’s a fad, or therapy is something that everybody's on. But as long as you have Jesus, as long as you pray to God, you will be OK.”

There’s also [this]: What goes on in the house stays in house, like nobody else should know your problems. Or we’ll be able to figure it out in-house, versus bringing somebody else in here to tell me about my issues.

I think another part that [factors] in, especially when I see Black families as clients, is that they are thinking that therapy is this big thing that is not right. They always see it as really dramatic on TV, but once they come into my office, or the office spaces I occupy, then it's like, “Oh, this wasn't what I thought it was going to be.”

And then, there are not a lot of culturally competent therapists out there. So if I'm Black, then do I trust sitting in front of a white therapist? Will a white therapist be able to relate to my issues and really understand what I'm going through?

Becoming a Trusted Resource in Philadelphia

I think when people see the work that we've done, we've been consistent over the years. So that if somebody were to check the records and say, “Well, why would I trust her?” they can look back on it and know I’ve had my program for this amount of years; I went back to school to get my degrees. So I can know what I'm really talking about — because a lot of people can make a video about mental wellness and self-care and coping skills.

But if I take you off the deep end, can I bring you back to shore? Do I have the tools to bring you back to shore? I think that's what separates me from a lot of people. I went back and got the education to back up the work I've been doing. Now we’re doing greater work.

Facing Community Response

It's been mostly positive. Every time we go somewhere, they say they weren't expecting to get what they got. I think it's mostly because a lot of times people don't want to have these hard conversations. They trust me enough to have the hard conversations, and to leave the people with something that's going to empower them, not leave them feeling down after a program, or after an assembly, or after a workshop.

Dealing with Pushback

One time I was doing a presentation at a school within a church, and there was pushback that day. We were talking about suicide. And this lady interrupted the presentation and was like, “Oh, you’re going to hell if you commit suicide, so just [to] let all you kids know right now, you're going to hell.”

Now I'm a licensed minister, too. And I'm liberal. I had to tell her, “No.” So we had a little back and forth conversation about that. But other than that, nobody has pushed back on what I've been teaching, or what's been taught, or what information has come through Dare 2 Hope.

Changes in Views of Suicide

When I first started Dare 2 Hope, nobody was really talking about suicide. It was still hush-hush. I remember getting calls to come to schools, and the principals would be whispering, “Can you come talk to my kids about suicide?” And I'm like, "Why are you whispering about it?" Why are we scared to talk about suicide out loud, upfront? And it bothered me, because so many people were losing their lives, or losing the battle to mental illness.

From the beginning — and I've been doing Dare 2 Hope for almost 10 years — I've seen the transition of people. Now [they’re] openly talking about their mental wellness, talking about why it's important to take care of your mind the way you take care of your body. So I think the stigma has kind of been — I don't want to say disappearing — but easing up a little bit.

Again, the harder work is with the older adults. The millennials get it, the Gen Zs get it. But I think the issue is still on those traditional, older adults who don't really accept the fact that they may have something going on in their minds that needs to be checked out. But I'm telling you, it definitely has been a shift in the right direction, as far as people caring about themselves. That includes their mental health, too.

Attitudes in Philadelphia versus the Suburbs

I think [suicide] has always been at the forefront in the suburbs. For the urbanized area, the North Phillys, the South Phillys, I think that it hasn't been touched on enough yet. I think we’re headed in the right direction.

But I think it has always been normalized in the suburbs. If we could just be honest, within white families and with white people, I think it's always been normalized, like therapy is something that just happened. Whereas in Black families, it's like, “Therapy, we don’t do that.”

Demographic Differences

Like I said across the board, millennials get it. I don't think a [college] degree makes a difference. I know people with degrees and people without them, and mental health is very important to them. I think it's generational, not educational.

Conversations with Colleagues in Other Big Cities

The same stuff that we deal with here is what people are dealing with other places. It is not really a difference, even when you look at the trauma from the crime. There’s crime happening in Philly, there’s crime happening in Chicago, there’s crime happening Baltimore, there’s crime happening in Florida. So the stuff our kids are facing is really the same across the board. [It’s] just coming up with different ways and different approaches to solving it.

I'm a solution-focused therapist, so I'm a person who’s going to use cognitive behavioral thinking. Let’s [understand] your mind, let’s change your behavior, but also how can we fix this? When I talk to my colleagues in other areas, it's the same approach: How do we get to the bottom of what is bothering or plaguing our kids in urban communities?

Coming Together to Find Solutions

We do many think tanks, and we get together and discuss cases, more so to try to get to the root [of the problem]. So we look at patterns of families.

If we see that this is a pattern, then how do we then prevent stuff from happening? If I know this family has generations of people not graduating from high school, or people not being able to get into the workforce and get good paying jobs, how do we prevent it? If this new baby's coming, at what age do we stop and prevent this? Where do we intervene in this family to prevent this person from going down the same path that the last two generations have gone down?

That's the work I love to do, when we look at patterns and try to figure out how we stop it from happening again and coming up with plans.

Biggest Challenges On the Horizon

Just finding the funding is always our biggest goal, because we need the money to continue to work.

And like I said, the stigma is breaking; people are investing more money in mental health and looking at mental health as an issue. I remember a couple years ago, I applied for a grant from the city to bring mental health therapists to the urban communities, and I didn't get the grant.

But this year, I put in [a grant application] because people have been focusing on mental health. Once in a while, cases have made national news. So I think that with the year that passed, people understand that if we get people's mental health regulated, a lot of things will change in the city.

Greatest Signs of Hope

We work in what some would call the worst schools in the city. We go to schools where kids have been kicked out of the public school system, and now are in an alternative school. But when I see a kid come in, in the beginning of the six weeks, all over the place, and then by week two, or week three, they’re working through whatever project we're working on in that particular week, and their attitude is starting to shift, they're processing their emotions better, they're communicating better, they're behaving better — that's the highlight for me.

Even with my clients, when I see them doing their homework and coming back a month from the time we start the session, and I can see the progress, that's what makes me want to continue my work, because we know what we're teaching is changing lives.