The Michigan Governor’s Race Through the Eyes of Three Very Different Communities

LAKE CITY, Mich. – Brad Seger knows this northern Michigan town inside and out.

A former mayor with roots that go back a generation, Seger can talk about logging in the area and the best time to tap the trees for syrup. He can go into the history of the church on the corner. And when the conversation turns to politics, he can explain how and why Republican Tudor Dixon will win this county in a landslide next week in the governor’s race.

“It’s going to go for Tudor heavily. The people I’m talking to, you know, they didn’t vote in the past, but they’re upset now, and they are going to vote,” he says in his deep baritone. “I’m just not sure about some of the decisions that are being made now are good for the country or the people. A lot of people here feel that way.”

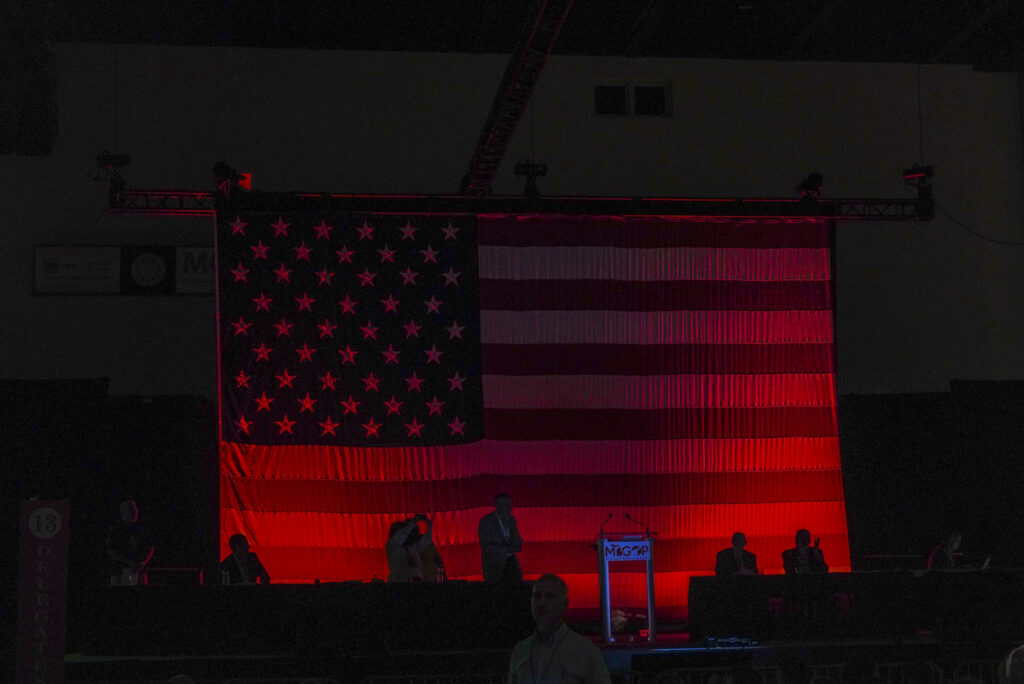

That’s not exactly a shocking prediction. Lake City and surround Missaukee County were made for Dixon. Former President Donald Trump won 76% of the vote in the county in 2020, the highest percentage he captured anywhere in the state. And Missaukee is not alone. It’s just one of a string of counties “up north” where Dixon will almost certainly clean up on November 8.

But that’s not the entire story, of course. Drive a few hours south and you’ll find communities that look 180 degrees different politically.

“We know (Gov.) Gretchen Whitmer is going to win Wayne, what we don’t know is by how much,” says Greg Bowens, a public relations specialist and one-time press secretary for former Detroit Mayor Dennis Archer who lives in Grosse Pointe. “And that’s a big question.”

In the two-color political palette that’s come to define American politics, Michigan is increasingly labeled as a “purple” battleground. But that color isn’t a single brush sweeping across the state: instead, it represents a complicated mix of very different kinds of people and communities, living in different political and economic realities and focused on different issues.

To study those differences the American Communities Project, based at Michigan State University, has been visiting with voters in three different counties this year. Those counties, Kent, Missaukee and Wayne, represent different kinds of communities in the project (the Urban Suburbs, Working Class Country and Big Cities, respectively). And as November 8 draws near, the voters in them have different issues on their minds.

Blue, Red and Purple

The point of visiting the communities wasn’t to reach swing voters or try to predict the outcome of the election between Whitmer and Dixon. The voting patterns in them are well established.

In the last two presidential elections and the 2018 gubernatorial race, deep-red Missaukee has not given less than 70% of its vote to the Republican candidate. Wayne, meanwhile is dark blue, and has given at least 66% of its votes to the Democrat in those races. In both counties the question is whether Whitmer and Dixon hit their targets on margin. And while Seger seemed pretty sure about Missaukee, Bowens, a Democrat, was less sure about Wayne.

“A cloud of nonchalant assuredness coupled with apathy is chilling the fall air,” said Bowens, adding that if nothing changes, “I think we might see some surprises.”

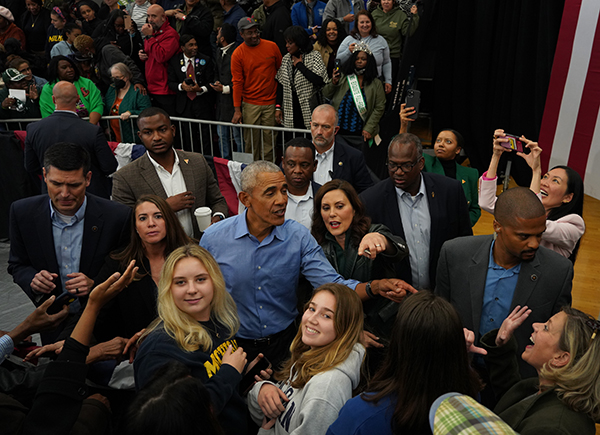

Kent is more representative of “purple Michigan.” Once reliably Republican, in 2018 and 2020 it voted for the Democratic option at the top of the ticket. It’s part of the larger story of the evolution of the nation’s two big political parties, suburban college-educated voters shifting to the Democrats. There are more than a few “former Republicans” there, like Neil Carlson, a principal at a consulting firm in Grand Rapids. Carlson says he voted for every Republican presidential candidate since he started voting in 1988, until 2016, when Donald Trump got the Republican nomination.

“I decided then that I will not bear this label anymore,” Carlson said. “I have never declared myself to be a Democrat, but long before Trump came along, I thought the Republican brand demand that I denounce and demonize the Democrats, and I know too many good people to do that.”

The question for Kent in these last few days before the vote is how many voters there are like Carlson in the county and how much Dixon reminds them of Trump.

But behind the enthusiasm in Missaukee, the angst in Wayne and the uncertainty in Kent is a set of issues that have defined the 2022 campaign in Michigan – and each looks different depending on the voters’ vantagepoint.

Kent County, the Urban Suburb

While Kent is known as the home of Grand Rapids, the city comprises less than 30% of the county’s population. Much of Kent is the suburban sprawl that flows out from the city – towns like Ada and Rockford, Wyoming and Kentwood. And while politics can be a difficult topic anywhere in 2022, that’s doubly true for Kent.

A lot of that is about the people who have moved into the county, says Mike Lomonaco, who was born and raised in the area.

“The influx of folks, families and whatnot, moving here, from Grand Rapids as well. It just kind of reflects that general change in the in the country (in suburbs),” he said. “I think, a big thing that’s happened in West Michigan and Kent County specifically, is it used to be that it was, you know, socially very conservative. Right? You certainly had fiscal conservatism and you still have the fiscal conservatism. But that social piece has changed a lot.”

Sergio Cira-Reyes represents some of the changes in the county, which saw its Hispanic population grow by almost 30% in the last decade. A community organizer in the Grand Rapids area, he says when he looks at Kent he sees a complicated community with divides running across a variety of different lines. In many ways, it’s very different from the homogeneity that once defined the area. “There is a lot of money here in western Michigan, but there are also a lot of neighborhoods that are disenfranchised,” he said. “It’s divided around race, but also around gender.”

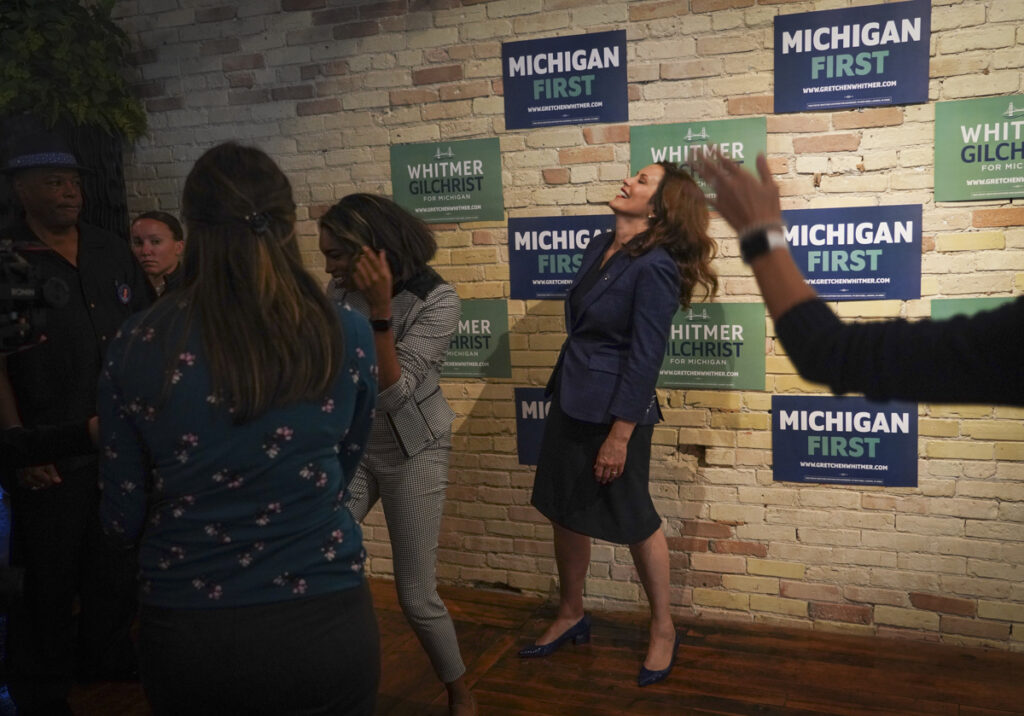

And those divides are likely to show within the county vote on Tuesday, he says. “A lot of women support Gretchen Whitmer. And communities of color are happy with how she was leading us during the pandemic.”

Voters of color now make up more than a quarter of the county’s population.

The suburb of Ada shows how population changes have remade the county in a different way. The township, which is the home of Amway, has grown by more than 40% since 2000.The large housing lots that define the community are still there, but an upscale downtown has popped up to change the feel and the township is good example of the new swing-voting nature of the county.

Donald Trump won Ada by about 13 percentage points in 2016, but fewer than 3 points in 2020. In 2018, Republican gubernatorial nominee Bill Schuette, more of a party establishment candidate, was a good fit for the township. He won it by 12 points. The question for 2022 may be whether voters in Ada and Kent see Tudor Dixon more like Trump or Schuette.

In terms of campaign issues, Kent County has ridden out the economic turbulence around COVID-19 better than many Michigan communities. As the state’s population growth has languished, Kent grew by more than 9% over the last decade. Its economic growth has been fueled by the medical and tech sectors. Its numbers for labor force participation and the time homes for sale spend on the market are essentially unchanged compared to pre-COVID-19 times. Unemployment is close.

And the pandemic itself, once a big issue here, has receded into the background, says Shana Shroll, who once served as a county commissioner here and now home-schools her children in Byron Township.

“I feel like if the governor’s race was happening in the fall of 2021, everybody was political. I mean, some people were like, ‘We need a mask on like kids are all going to die’ and then other people were like, ‘Gag my five year old? This is an outrage.’ … that felt very, very close to home for a lot of people.” But much of that tension is gone now, she says. “I think that it speaks to like how short people’s attention spans are.”

Most everyone will tell you the abortion rights will be a big issue here, with a proposal to enshrine them in the constitution on the ballot, but how it will cut is far from clear. The main issue for voters here is probably how palatable they find Dixon.

Wayne County, the Big City

The story is different in Wayne, the most populous and most diverse county in the state. Detroit makes up more than a third of its population, but even the suburbs within the county, places like Dearborn and Livonia, are densely packed, making Wayne home to a big block of urban votes. In 2020, the vast majority of cities and townships in the county went for President Joe Biden, a Democrat who carried 94% of the vote out of Detroit.

One result of all that dense “blue” urban vote is people are generally engaged with politics and most feel pretty confident that Whitmer will win on Election Day, powered by a pro-abortion-rights vote.

Dr. Shauna Diggs, a dermatologist in Wayne County, says she’s had frequent discussions with her patients and staff about abortion and the campaign. “Most of the people I talk to are pro-choice, but not for abortion for themselves,” she said. “I think that’s a driver for voting, and how they vote. I think it might drive people to the polls. And I think it might end up being a decision maker for who they vote for, because what other issues are there, it’s become the predominant issue.”

Others in the county cited abortion as a top issue as well. Wayne and Detroit often face economic struggles – and in many ways they still do – but comparatively speaking, the county has fared well post-COVID-19. The August unemployment rate for metro Detroit was a scant 3.5%. Other than November of 2019, that’s lowest unemployment figure in the area since 2001.

Those good numbers may have freed up voters to focus on other topics, but abortion carries weight in different ways here.

Dante Williams, who owns Cutz Lounge in Detroit, says he is personally opposed to abortion, but doesn’t think the procedure should be illegal. “For women this is ‘It’s my body and you can’t tell me what to do with my body,’” he said. “And this isn’t just about young people or people without children. You could be a mother of four and you have the fifth kid coming and you know you can’t afford it.”

He says he’d lived through the issue personally with a former girlfriend when he was young. She got pregnant and decided to have an abortion, he was opposed but supported her through the process. The two split up after, but he said he has no regrets. “It wasn’t my decision to make.”

West of Detroit, Dearborn always holds special interest on election nights. The city holds some 100,000 people and more than 40% are Arab, according to the U.S. Census, and they can be driven by different kinds of issues, particularly about how their community is treated by elected officials.

Dixon could have some support here for a few reasons. Even if tensions ran high between Arab Americans and the GOP under Trump, many Arab voters are socially conservative.

On top of that, Dixon, who is part Lebanese, could use her heritage to connect with the community, but so far has not, says Machhadie Assi, a Lebanon-born victim’s rights advocate who lives in Dearborn.

“Dixon is someone who has never reached out,” she said. “I’m talking about Wayne County. Some people don’t even know what she looks like, they don’t even know her name. They don’t know who the Republican on the ballot is because she hasn’t reached out to the community. … Forget about what she stands for, people don’t recognize her name.”

Assi says there more conservative elements in the Arab community that don’t agree with Witmer on some issues, but ultimately, she doesn’t expect them to vote for Dixon. “They’re just not going to vote,” she said.

One point worth noting, however, is even in mid-October many contacts in Wayne – Assi, Diggs and Greg Bowens – said voters had not tuned into the race yet. For Democrats, that could be a flashing warning light for Whitmer.

Missaukee County, Working Class Country

There are different ideas of where “up north” begins in Michigan, but Missaukee County fits the bill under most definitions. South of Traverse City, but north of the Zilwaukee Bridge, it is a rural community of 15,000 people just east of Cadillac. And that setting and population has impacts on daily life. Missaukee and counties like it are places the economy may be a real driver this election.

Places like Missaukee have had different kinds of challenges with inflation. One in every five residents is 65-or-older here and many of those people are retired and living on a fixed income, many in small homes scattered around Lake City. Seger himself is one of those people. And when prices rise those voters often find themselves trying to stretch their dollars with no way to increase income.

“Nobody likes to see $4.50 gasoline. I mean I’ve been retired for 14 years, and my pension is $35,000 a year, that’s gross,” Seger said. “I can live frugally, always have and been fine for the last 12-plus years, but this past year, my pension is not worth near what it was in the past.”

Add in the fact that up here many people drive pickup trucks or four-wheel-drive vehicles out of necessity and the impact of this year’s hike in gas prices hits especially hard.

Along with lumber and farming, Missaukee relies heavily on tourist season, which was impacted by COVID-19. Lake City’s quaint downtown, marked by restaurants, the upscale 2 Moon Bakery and the Tasty Treat ice cream parlor (home of the “Largest Cones in the North”) sits next to Lake Missaukee. The town doesn’t get the big money visitors of, say, Traverse City or Petoskey, but it draws a steady stream of summer travelers, many of whom stay at the small, family-owned Lakeview Motel.

The motel, run by husband-and-wife Greg and Natalie Davis, had a great summer, but to keep up with inflation they raised nightly rates by 30%. Occupancy was up five percent, but gas for boats at the Lakeview Marina went from $5 a gallon to $8 a gallon, hitting area boaters hard. Those memories have lingered into the fall.

But Greg Davis, one of the few Missaukee voters who pulled a lever for Biden in 2020 says the economy isn’t the real issue. “Whitmer has no chance here. It will vote 75% for whoever the Republican is and the same 25% will vote for the Democrat,” he said. “That’s just how it goes.”

Davis says the community is hard-wired with an anti-regulatory “don’t tell me what to do” sensibility, another reason its GOP lean is so strong. “Even when it comes to washing your boat before you put it in the lake. We tried that rule and resistance was huge. People said, ‘I’m not washing my boat.’”

That attitude was also present during the pandemic. Many in the community held off on getting the COVID-19 vaccine until David and Paul Ebels, well-known brothers who ran an area hardware store died of it. And Missaukee still has one of the lower vaccination rates in the state; about 53% have received one dose, compared to roughly 69% statewide, according to state data. Talk to voters here, however, and the bigger issue was the way the state clamped down on boating during the pandemic.

Ultimately that distrust of government will drive the vote here next week. It’s not that voters here say they love Dixon, they just really don’t like Whitmer and they plan to make their voices heard.

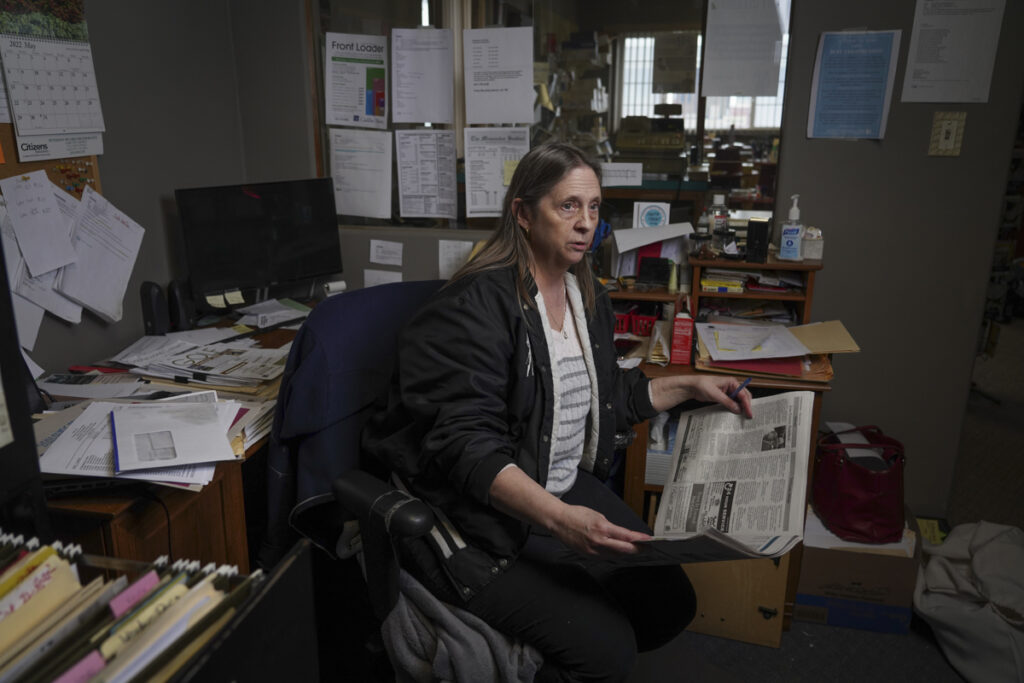

Jill Thomas, the office manager for the Missaukee Sentinel, the local weekly newspaper, spends much of her day talking to people in the community and that’s all she’s been hearing. Thomas doesn’t just man the phones, she takes ad orders for the paper in the office, which does everything from handling local dry cleaning to doing measurement for prom tuxedos.

“I didn’t vote for Dixon in the primary, I was a little leery about her. I have a tendency not to trust women because of all the b.s. I put up with from females in school – they can be major b*****es,” she said. She’s still not thrilled at her choices on the ballot she says and would like a third-party option, but doesn’t want to waste her vote. “In the end I guess I’m going to vote for [Dixon]. She’s the lesser of two evils.”

Across the northern half of the state, that sentiment will likely be repeated in the next week and time will tell if that will be enough to change who sits in the governor’s mansion.

There are 83 counties in Michigan. When the state’s presidential vote “flipped” from Trump to Biden in 2020, only three of counties voted differently than they had four years previously.

Michigan may be a purple state, but the final hue it takes on November 8 will likely depend on how deep the reds are in places like Missaukee, how much blue vote turns out in Wayne and which color Kent is on election maps when all the votes are tallied.

(A slightly shorter version of this story appeared in the Detroit Free Press the weekend of Nov 5 & 6)