In Pennsylvania’s Exurbs and Urban Suburbs, Political Organizing Has Been Intense Since 2016. What Could It Mean for 2020?

There’s a lot of speculation about which demographics will be key to Democrats’ fortunes in 2020. What those analyses rarely discuss is the space where political change actually happens: the local social contexts in which individual voters experience politics, including the 2020 election cycle.

Voters’ perceptions aren’t formed in a vacuum. What we hear about candidates, how we feel about what we hear, and what we do about our feelings are all shaped by the personal networks in which we live. Campaign professionals tend to treat the social and organizational terrain as a given and put up the best numbers they can. But the social/organizational context isn’t a constant — or a given. It is a built environment. And in recent years, that terrain is being remade.

The remaking is not uniform, but patterned across space in consistent ways. In Pennsylvania, where I live, grassroots organizing in reaction to Donald Trump’s 2016 election has been most intense in the Urban Suburbs and Exurbs.

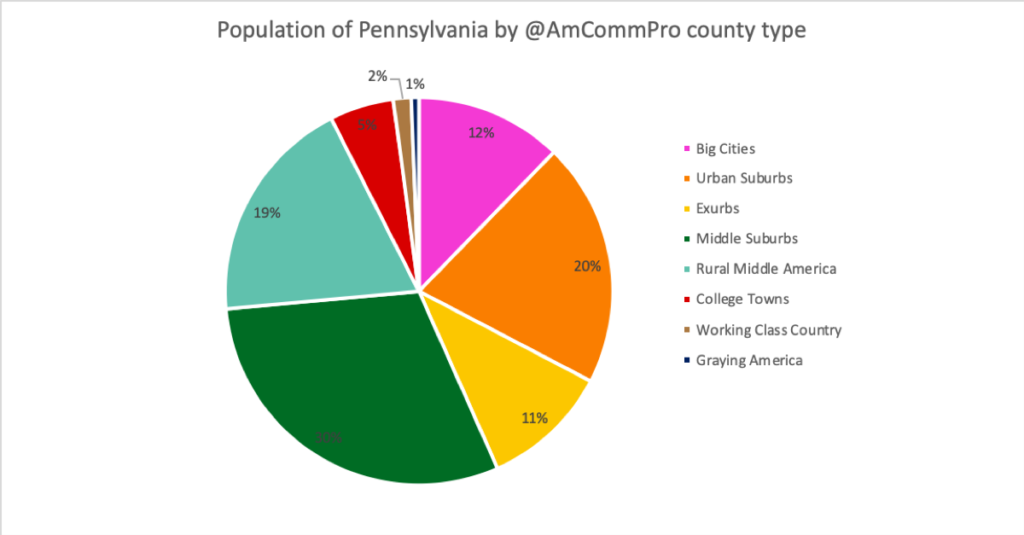

In Pennsylvania, what happens in the Urban Suburbs and Exurbs has a major impact statewide: Together the two county types account for one-third of the state’s population.

Understanding the Breadth and Depth of Mobilization

It’s well understood that grassroots mobilization since Trump’s election has centered in the suburbs and been led by suburban women. But systematic analyses that identify which suburbs, how great their mobilization, and their consequences have been scarce.

A good place to start: Count and map the groups listed in Indivisible’s “Find your local group” portal, almost all first posted in the first half of 2017. The organizations listed are a grab bag. They include some local progressive groups that antedated Trump’s election, others that seem never to have come into existence, and still others that exist solely as information exchanges, such as Facebook groups or email lists. But one-third or more of the groups listed have thrived. Relying on Indivisible HQ more for moral support than marching orders, they have dived into municipal and regional politics, marshaling volunteers to lead ballot initiatives and challenge incumbents from township coroners to U.S. representatives.

Meanwhile, most counties or congressional districts we studied show additional post-2016 grassroots groups that never listed themselves on that portal. While the Indivisible portal is not a complete guide to the grassroots groups active in any given locale, it is the best rough indicator of the local intensity of civic activism in reaction to Trump’s election.

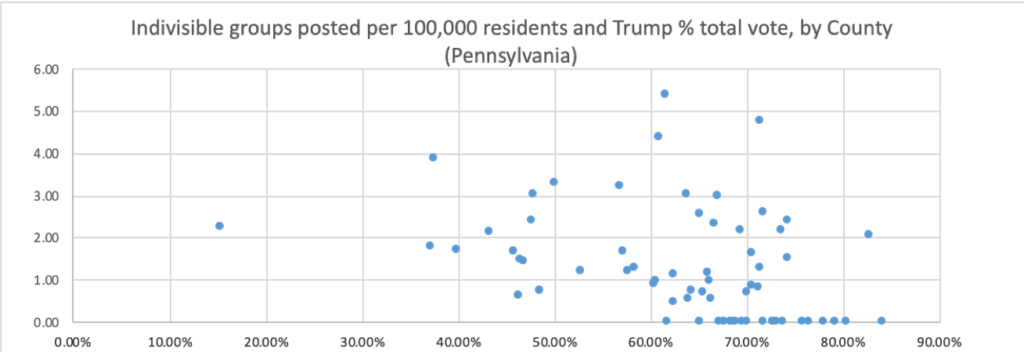

One might have thought that the pace of group formation would simply reflect the number of Clinton voters in a given locale. But that’s not the case, as this scatterplot of Pennsylvania counties shows. The 20 counties with no groups posted did vote heavily for Trump. Almost all of them are very small and very rural. Beyond that there is no correlation.

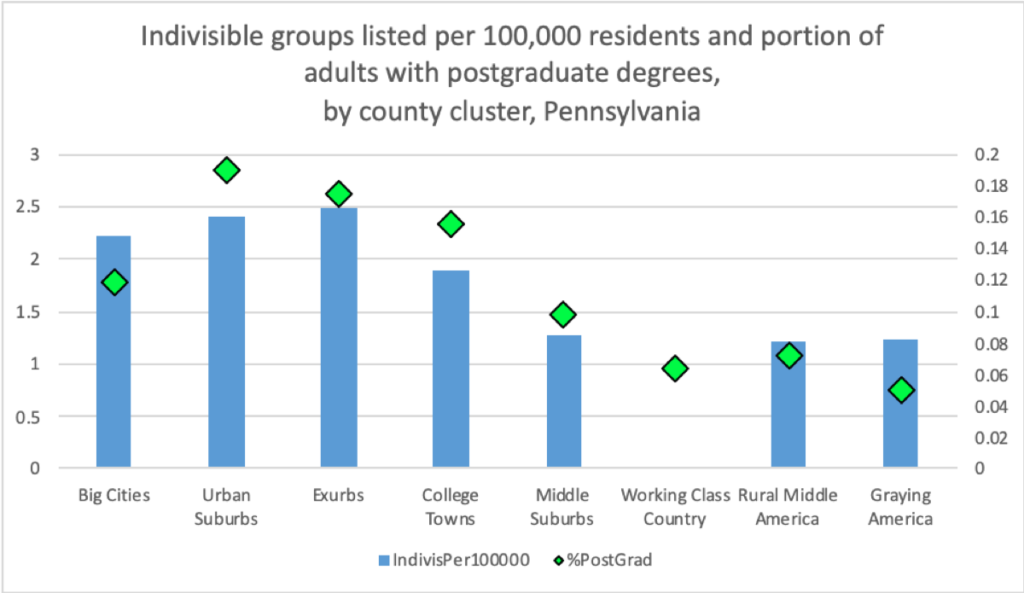

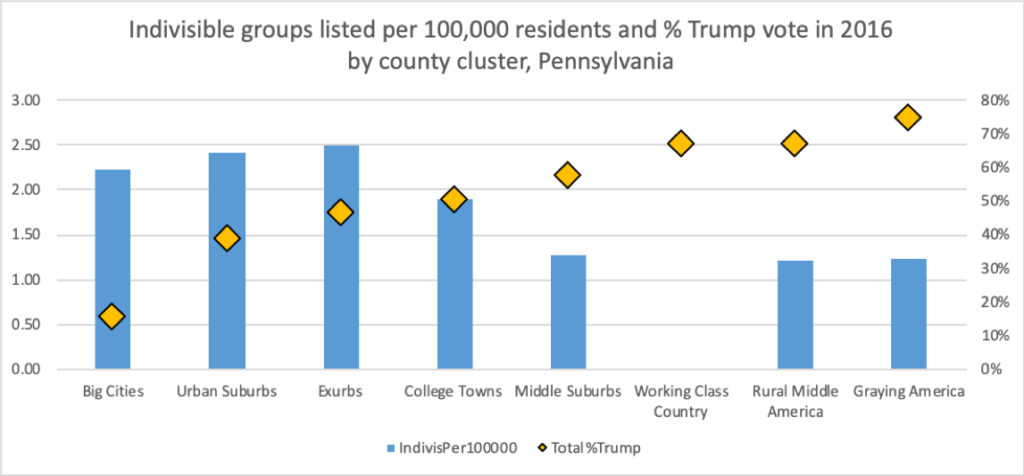

When aggregating listings by county type, a systematic pattern emerges — here again, it is not simply a matter of partisan prevalence.

- Big Cities had lots of listings. (In Pennsylvania, Big Cities include only Philadelphia County.)

- Urban Suburbs and Exurbs had even more.

- Middle Suburbs, Rural Middle America, and Graying America had about half as many.

- Across the nine (very small) counties representing Working Class Country and Graying America in Pennsylvania, a single group contact was posted.

Rather than partisan lean, what the per capita frequency of Indivisible listings is most highly correlated with is the portion of adults with master’s degrees or higher in the county. This correlation between per capita frequency of Indivisible listings and postgraduate educational attainment is even stronger than its correlation with three closely related characteristics:

- the portion of adults with college degrees,

- median household income, and

- how rural the county is.

Surging Democratic Power in the Exurbs

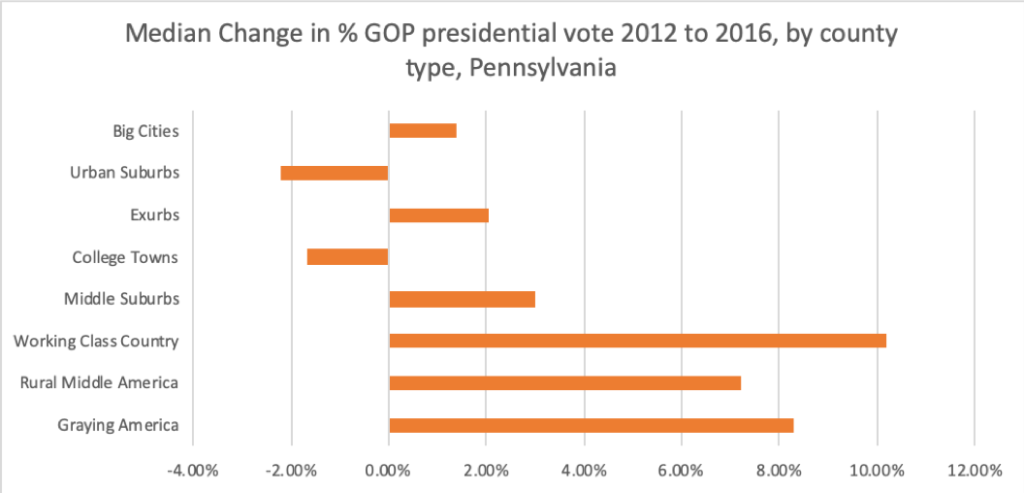

It’s worth remembering that the strength of anti-Trump activism in the Exurbs — disproportionately well-educated and traditionally Republican — was not a forgone conclusion in 2016. In the Exurbs, Trump actually performed slightly better than Romney, although not as strongly as he performed in the Middle Suburbs or, to an even greater degree, Rural Middle America, Graying America, and Working Class Country.

So Pennsylvania’s Exurbs were home to significant numbers of people who weighed Donald Trump against Hillary Clinton and chose Trump. But the Exurbs were also home to many people — retired and professional women in particular— who were appalled by that choice. And they haven’t stopped organizing since.

Since we don’t have unified statewide (much less nationwide) granular data on campaigns for offices like township supervisor or school board, it’s hard to track systematically the change in the texture of local political life in the middle-to-upscale suburbs: both the denser, peri-metropolitan Urban Suburbs, and the more diffuse and demographically homogeneous Exurbs.

When studying local reporting, however, the surge is clear. In both Urban Suburbs and Exurbs, new grassroots groups have poured massive energy into down-ballot races, including town and county councils and school boards. That activism on behalf of Democratic contenders has been particularly revolutionary in the Exurbs, where down-ballot offices had long remained in Republican hands. For example, in Chester County, no Democrat had ever been elected to a county “row office” in its 300-year existence. Things changed in 2017 when four offices were up for election, and Democrats flipped all four.

What Happened in 2018 and 2019 Elections

That organizing — not just energy — just accelerated in 2018. It spurred Conor Lamb in a March 2018 special election in a congressional district that Trump had won by 20 points. Grassroots women from the Urban Suburban and Exurban stretches of the district pounded the pavement in their own neighborhoods and spent weekends canvassing communities farther afield. In 2019, some of the same groups helped flip a state senate seat in that region, knocking doors overtime to keep GOP margins as low as possible in the district’s wealthiest, most conservative parts.

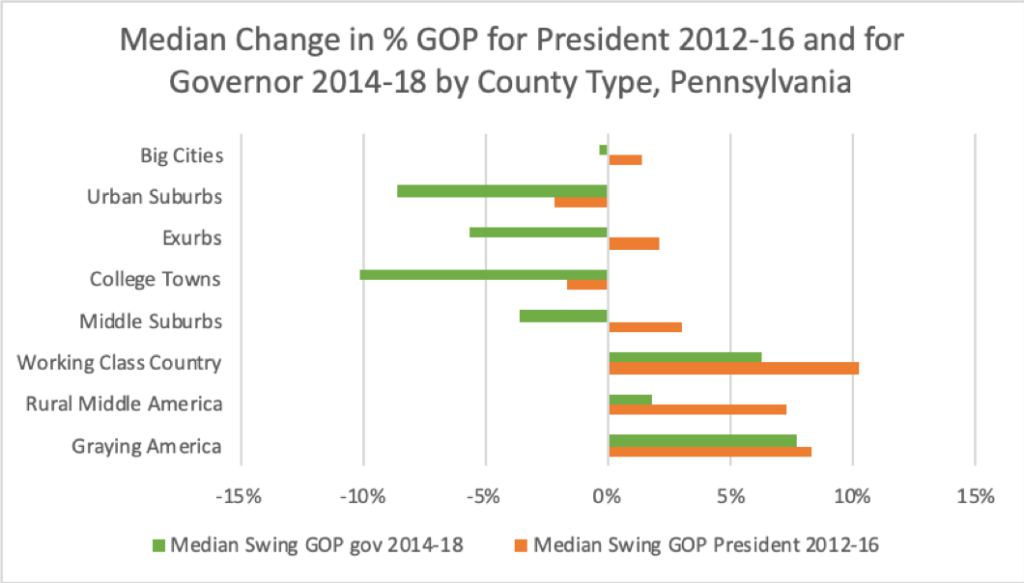

So how did Trump’s gains over Romney hold up in the nationalized contests of the 2018 midterm elections? For two years, retired teachers, librarians, and Girl Scout moms had founded groups, recruited candidates, and canvassed across Pennsylvania’s Exurban and Urban Suburban counties (and in parts of other counties most like them).

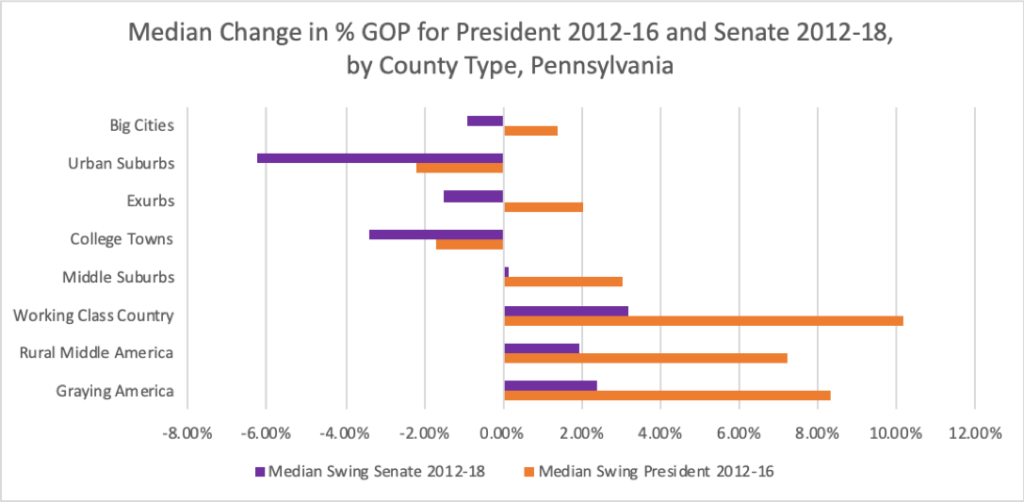

Republican gubernatorial challenger Scott Wagner did not match Trump’s numbers in any county in the state — and fell short by double digits in 12 counties. Meanwhile, Republican Senate challenger Lou Barletta, who claimed to be “Trump before Trump,” campaigned on his anti-immigrant record as mayor and congressman — and lost to incumbent Sen. Bob Casey (D) by 13 points.

When looking at which Pennsylvania counties’ votes had shifted since this senate seat and governorship had last been contested, stark differences appear across county types.

Gubernatorial Race

Gov. Tom Wolf (D) lost ground from where he stood in Pennsylvania’s rural counties four years earlier.

- In Graying America and Working Class Country, the Democrats’ decrease in support continued at close to the 2012-2016 pace.

- In contrast, in Rural Middle America counties, Wolf’s decline in support was far less steep than what Clinton had faced in 2016.

Elsewhere, Wolf gained ground.

- In Philadelphia County, a Big City, Wolf slightly improved his margin from 2014.

- He made large gains in the Exurbs and Urban Suburbs.

- He significantly improved in two College Towns — Cumberland and Dauphin counties — adjacent to the state capital, Harrisburg.

- In the populous Middle Suburbs, Wolf’s gain from 2014 to 2018 was as large as Hillary Clinton’s decline from what Obama’s 2012 showing had been.

Senate Race

Pennsylvania’s senate race had the same geographic profile. How much of Trump’s 2016 gains over Romney in 2012 did Barletta hold as gains over Casey’s showing in 2012? Barely any, even in the most rural, aging counties.

In the Urban Suburbs, senate results showed Democratic commitment powering forward. These counties had swung hard against Trump, yet were still nowhere near a ceiling in 2016. Meanwhile, the Exurbs, which had edged rightward in 2016, saw Democratic gains in 2018 not just compared with 2016 but also compared with 2014 and 2012.

An Antidote and a Call

What happens in Pennsylvania’s Urban Suburbs and Exurbs is a big deal — for state politics and for America’s electoral college. And paying attention to the local social and organizational terrain in electoral politics should be an important antidote to the demographic determinism that poll-driven commentary can imply. The electoral shifts that have occurred since 2016 are not geographic or demographic destiny, but the result of thousands of hours of mostly-invisible volunteer labor building on preexisting networks of connection. These local webs of communication and commitment will shape voters’ experiences of the 2020 campaigns. For people worried about outcomes in 2020, that should call them to action right now.

Lara Putnam is UCIS Research Professor and Chair in the Department of History at the University of Pittsburgh. She is active in grassroots political organizing in southwest Pennsylvania.

Lara Putnam is UCIS Research Professor and Chair in the Department of History at the University of Pittsburgh. She is active in grassroots political organizing in southwest Pennsylvania.