An Opportunity to Close the Digital Divide in Michigan College Town

One in four residents in Michigan’s Ingham County do not have internet access, according to a new report co-sponsored by Ingham County’s Broadband Task Force. It’s a startling figure for a county that’s home to the state capital and the state’s largest public university, Michigan State.

Since 2022, the task force has been working with the Merit Network to survey county residents about their broadband internet access, and the group released its report to the public in November 2023.

Much of Ingham County lacks the infrastructure — wires or towers — needed for fast, reliable internet. The report found that 28% of residents have no internet access at all. More than 60% of those respondents said infrastructure was the biggest reason they weren’t connected.

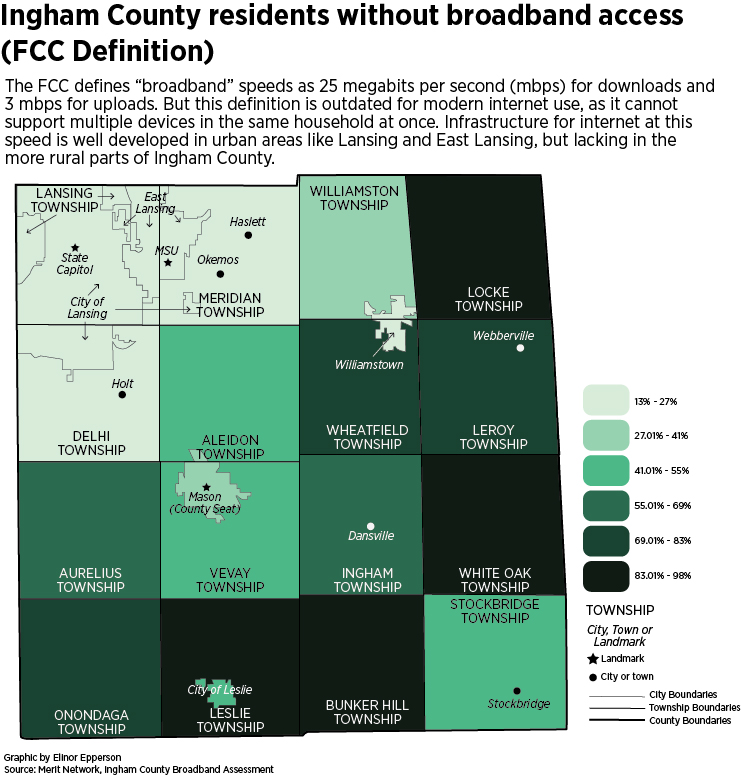

These numbers contrast sharply with previous data from the Federal Communications Commission, which estimated that as much as 98.5% of Ingham County is equipped with access to broadband. But this data, largely taken from providers at face value, obscures persisting gaps in coverage.

Different Vantage Points

Librarians like Amanda Vorce have seen patrons struggle with this problem for years. Starting at the Capital Area District Library in April 2020 felt like being on the Titanic, she said.

“It honestly felt like passing out lifejackets to the drowning,” Vorce said in an email. As head librarian at the Webberville branch, she is responsible for helping families check out mobile hot spots. These devices convert a cellular network signal into a wireless internet connection that nearby devices can use.

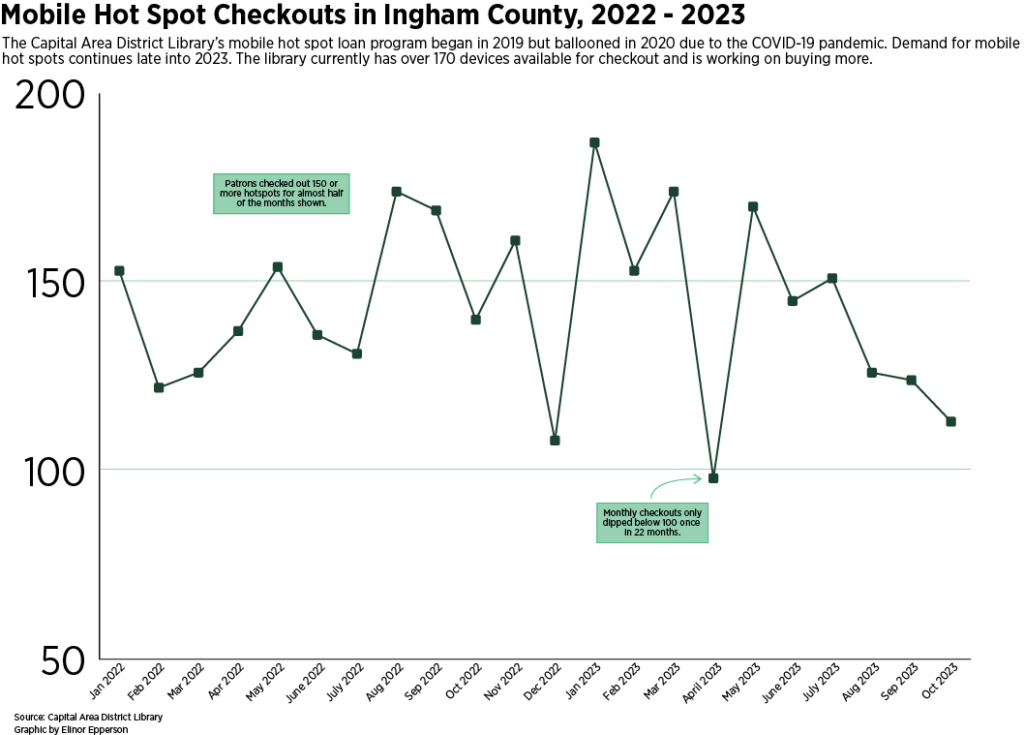

The program existed before Covid-19, but demand skyrocketed once school and work moved online in 2020.

“What was already a problem with internet here became a dire problem,” Vorce said. She described a “mad scramble” to get hot spots to as many families as possible.

“I thought that [the hot spots] would just be a Covid thing, just a temporary solution,” Vorce said. “But what we found was that it’s a problem that keeps going so we still have the program.” The hot spots are one of many tools patrons can check out from the “Library of Things,” and they are one of the highest-demand items in the library’s catalog.

The digital divide looks different depending on where you live, said Keith Hampton, the academic research director at the Quello Center at Michigan State University. “There are no wires in the ground in many rural areas,” Hampton said. “And so, there’s just no way to go online, even if you have the money to pay for access.” In urban areas like Lansing and East Lansing, the biggest barrier is usually affordability.

Hampton co-authored a recent study about the continuing digital divide in rural Michigan. The study found broadband access rose during the first year of Covid-19 and remote schooling but has since declined. Efforts like the library’s mobile hot spot program and other emergency measures coordinated by public schools were largely responsible for the temporary peak in access, he said.

“It’s a nice little Band-Aid bridge,” Vorce said. Patrons can check out hot spots for as long as six months — but it is not a long-term fix.

A Slice of the Pie

Ingham County wants to close that divide. County Controller Gregg Todd said funding is a big part of the solution.

“At the end of the day it all comes down to money in one form or the other,” he said. Todd is also the chair of the Ingham County Broadband Task Force, a committee that reports to the county commission. The task force formed in 2021 and has been using a portion of Ingham’s American Rescue Plan funds to determine how to get broadband internet to as many residents as possible.

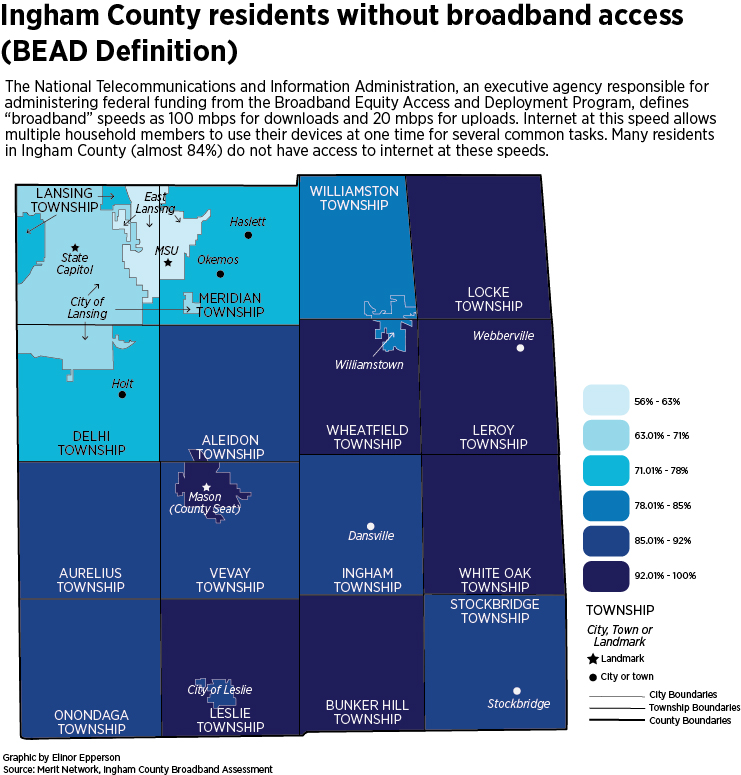

The task force focuses on applying for funds from the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program, colloquially called BEAD. The program is part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act signed into law in November 2021.

Earlier this year, BEAD’s $42.5 billion pot was distributed to states to build infrastructure in unserved and underserved areas of the country. Michigan received $1.56 billion from BEAD —the fourth highest allotment in the country.

To apply for funds, counties must provide data that shows how many residents are unserved and underserved.

Speed Is Key

The National Telecommunications and Information Administration — the executive agency under the Department of Commerce administering BEAD funds — defines “unserved” and “underserved” based on the speed and quality of internet access a consumer receives.

Internet speed is measured by how much data moves between a connected device and the network — how many megabytes per second (mbps) the user can download or upload using the connection. Before BEAD, the FCC defined broadband internet as 25 mbps download and 3 mbps upload.

But these speeds are often insufficient for modern internet use. Many households, especially those with children, need internet for several devices at the same time.

The mobile hot spots available from the library vary in speed from 5 to 25 mbps download speed, barely reaching the FCC’s threshold. Hampton said too many hot spots near one tower can exhaust the available bandwidth, slowing the connection for everyone.

If Ingham County receives BEAD funds, it will need to build internet connections that can reliably reach speeds of 100/20 mbps at an affordable price for consumers, what the National Telecommunications and Information Administration terms “low cost.” These speed thresholds define “unserved” (below 25/3 or no internet at all) and “underserved” (below 100/20).

Mapping Ingham County

The task force partnered with Michigan Moonshot, an initiative of the Merit Network, to administer a survey and speed tests in 2022. The survey reached more than 5,000 residents, many of them in the less populous townships on the county’s edge.

Merit found that 50% of residents are unserved. Most respondents (almost 84%) are underserved. Of residents surveyed who did not have access to broadband, 64% said the primary barrier was availability (“wires in the ground”).

About 24% of respondents reported that cost was the biggest barrier. A map of Lansing’s respondents showed most had options to connect to the internet but did not have it for reasons other than availability.

Comparing these numbers to the rest of the state is difficult, as the Michigan High Speed Internet Office has historically relied on FCC data. In its 2021 five-year plan for BEAD funding, the office estimated there were at least 490,000 households unserved or underserved — about 12% of Michigan’s households.

Todd said the FCC has since updated their methods and the most recent data from October 2023 should be more accurate. Those numbers indicate that most Michigan households (almost 94%) have access to internet that reaches 25/3 mbps. But Merit remains skeptical and is creating a tool to help local governments and residents challenge this data when the state office reviews it in January 2024.

Beyond Infrastructure

While BEAD funds will not solve the digital divide, they are a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for many communities.

“There’s never been this many resources put into attempts to create equity and infrastructure for access,” Hampton said. Todd and the task force are looking to “maximize” the funds they receive. The county recently hired Urban Wireless Solutions to determine the best options for providing internet access to the most people using Merit’s data.

Todd said that could mean providing incentives for internet service providers to install cable to the county’s more remote areas. Other options include broadening the county’s wireless infrastructure by erecting more towers or installing equipment on existing water towers.

The library’s 170 mobile hot spots are still in high demand. Waitlists extend into the hundreds for both short- and long-term checkouts. Todd expects BEAD funding to become available in June 2024 — if Ingham receives it.

If county residents do not have adequate broadband coverage now, Todd says they should reach out to him via email.

This is part of a series of posts from students at the Michigan State University Journalism School. The students will be covering four counties around Michigan during the 2024 campaign for the Detroit Free Press working with the American Communities Project typology.