Texas Hispanic Centers on the Border of Change

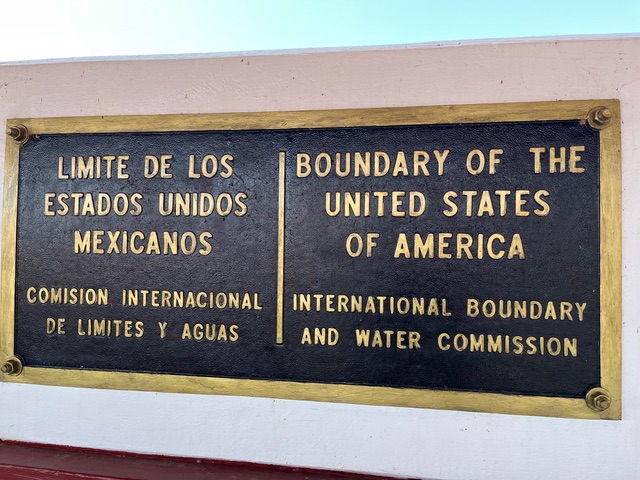

When you look at a map of the world, it makes an unspoken proposition: that borders separate peoples and nationalities and languages and cultures as neatly as their lines and colors set them apart on the map. The world is, and has always been, more complicated than that. Strict observance of borders may have legal power, to describe and delineate authority, responsibility, and possession. But borders do not describe the human condition nearly as well.

In the spring of 2025, just a few months into the new presidential administration, the border continues to be a place of focused attention, controversy, and commerce. It is also home to a never-ending cat-and-mouse game between the U.S. government, and criminal gangs running billion-dollar businesses, shuttling drugs and people north, and guns south.

Need clothes for the new school year? Head north.

Need a crown for a broken tooth? Need lip-filler, or a drug your insurance policy won’t cover without a massive co-pay? Walk south.

Want to take advantage of cheaper home prices south of the border, and better wages north of that line? Live in Reynosa, Nuevo Progreso, or Ciudad Miguel Aleman, grab your credentials and cross an international border every weekday morning to head to the third grade, or to a job in trucking or construction, in the United States.

In Rio Grande City, the largest jurisdiction in rural Starr County, one big-box retail parking lot saw every third car from a northern Mexican state. This is, in so many ways, one place. But one place with a line running through it. And that line can make simple things complicated.

For all that, the border is very much open for business. To the relief of politicians, developers, and business interests. At the same time — the Border Patrol will tell you — for the cartels controlling human trafficking operations at this part of the border, business is bad. Reported with satisfaction in Washington, and affirmed all along the vast frontera, border crossings are way, way, down.

Hispanic Centers’ Economic Development

A long string of Texas counties hug the Rio Grande and Texas’ huge 1,254-mile-long border with Mexico: from El Paso County in the northwest, tucked under a little piece of New Mexico, snaking all the way south and east through Presidio and Brewster, Webb and Zapata, down to Starr and Hidalgo, some of the river’s final destinations before it spills into the Gulf of Mexico.

178 Hispanic Centers

In the matrix used by the American Communities Project to define the nation’s counties, the jurisdictions hugging the Rio Grande are almost all “Hispanic Centers,” places where self-identified Latinos make up the largest share of the population, on average 53%. In the case of Starr and Hidalgo counties, the share is above 90%, making these some of the most uniformly Latino counties in the country. In the 2020 census, rural Starr stood at 97%, more urban Hidalgo at 91.9%.

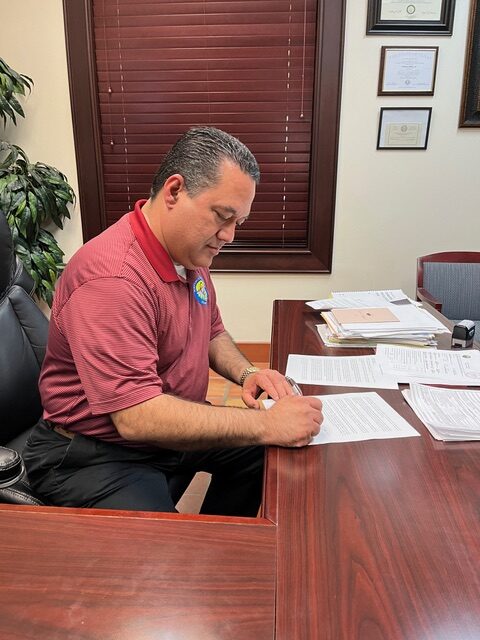

There’s a bustling border crossing in Starr County’s seat, Rio Grande City. You could easily walk to the border from the domed government building in Rio Grande (pop. 15,317). The city manager, Gilbert Millan, told me Rio Grande City has worked hard to attract retail outlets that appeal to shoppers on both sides of the border, and it shows on his balance sheets. “We have had a historic tax collection year. Last year, we did over a half a million. This year, we’re close to 800,000. I’m sure you saw on the way in…we didn’t have Starbucks, or Chick-Fil-A three years ago. We are just booming!

“You ask me about the tariffs. We will see when they come. We have a port of entry. And a lot of these shoppers are coming from across the border. We get the benefit of the people coming from cities like Ciudad Camargo, and Monterey, because we just have so much variety now. They come here and shop and go back to Monterey,” Millan said.

City managers are combinations of civic boosters, like their mayors, and very much green eyeshade people, watching the money, worrying about roads, sewers, and payrolls. Millan ticked off the list of recent developments: a new hospital, a new McDonald’s, a Ross, a Marshalls, a T.J. Maxx. Starr County is, by American standards, exceptionally low income. His town sits on an east-west arterial road, away from the heavier traffic of McAllen, just over the border from Mexican shoppers, and brings throngs of shoppers to what is a tiny municipality. Millan is counting on rising revenue giving the city the money it needs to improve infrastructure, raising yet more revenue and encouraging a virtuous cycle. On the wall of his office is a picture of his son showing him in the uniform of the local high school’s football team. Would he encourage his own son to come back to Rio Grande City after college? “You don’t have the opportunities, obviously, that the bigger cities have. I think we’re getting there. We’re getting to the point where we’re seeing these franchises and national businesses.”

Continue up US-83 from Rio Grande City, past fields and forests bursting with green (after six month’s torrential rain fell in one day earlier in the week) and you reach Roma, Texas, smaller than the county seat at just 11,500 residents. It, too, is home to a busy border crossing. It is also a lesson in development economics written in asphalt, brick, and mortar.

There is no HEB, Ross, or Walmart. There is no shopping center just a quick hop over the border. Most of the businesses along the commercial strip are family-run. There is not enough money, commercial activity, or steady enough demand to support national brands here. Angie Salinas Canales has lived here her whole life. “We have lots of mom-and-pop grocery stores that still work the old-fashioned way where they say, ‘I’ll finance it for you. When you get your check at the end of the month, come and pay me. Remember how many of our citizens are on Social Security and how can somebody survive on $500 a month?”

Land and buildings are so cheap that when a business fails, there is little interest in moving new enterprises in. When I met Salinas Canales, senior vice president of Citizen’s State Bank of Roma, over lunch, I asked her to give me an “elevator pitch,” to sell me on Roma. She had a tough time. “The landowners that are willing to sell are hiking their prices through the roof.” If land is expensive, and the cash flow unsure, she said, no national brand will open here, even with the steady stream of trucks coming up from Mexico. One possibility for economic development, Salinas Canales said, comes from truck maintenance and repair. For the local students who do well in the local high schools, there is not, she concedes much to keep them in Roma. The academically inclined head to Edinburg’s branch of the University of Texas system, UT Rio Grande Valley, to Austin or beyond. The ones who are good with their hands head for the oil and gas fields, in East Texas, North Dakota, and elsewhere throughout the West.

Two Sides of the Border

At its old core, away from the roar of US-83, the Texas side of the river sits high over the Rio Grande. Here, the two sides of the border were once one town. They are still connected by commerce, and blood ties; by an accident of history, they find themselves on two sides of an international border. The Rio Grande is so small here it practically looks like you could hop across. That leap would probably attract the attention of the Border Patrol, sitting on a high point with a broad view of the river. The old town center has an old plaza, a church, and an interesting collection of 19th-century brick buildings scattered around it. In a more active economy, it might already be spruced up, gentrified, and attracting tourists and locals. Roma’s trying. There’s a bird watching center, attracting birders who value this busy highway in the sky for the airborne migrants who don’t worry about papers. There is a small distillery selling and shipping locally made agave. Most of the town, however, looks empty.

Salinas Canales told me it is easy to see unauthorized border crossings are way down. “I don’t see as many illegals coming in as we used to. They would hide in our plants. Even walk into our bank and hide there, because the bank is right on the border. I don’t see that anymore, but what I do see is a lot of Border Patrol, and the county sheriff, parked along the riverbank in the evening. And of course, you hear the gunshots of the warfare going on across the border.”

The Rio Grande was not always a border. For centuries the Spanish Empire’s Viceroyalty of New Spain and later the Republic of Mexico was on both sides of that meandering waterway, flowing almost 1,900 miles from Colorado and out to the gulf. These days it marks an international boundary, but a porous one, with communities on both sides dependent on its permeability.

Daily Life in a Cornerstone Region

Along with the heavy Latino presence, there is poverty. Hidalgo is the heart of the poorest Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area in the U.S. The per capita income in the metro home to McAllen, Texas, to the formidable border infrastructure and huge strip malls is just $33,412. The per capita income for Americans as a whole is $64,170. For the city of McAllen itself, per capita income is just $29,406.

What does this mean in practice? How do these numbers shape the daily life of counties like this? For one thing, home prices are low. In a state that already acts as a magnet to other U.S. regions because of affordable housing, the median home value in McAllen is around $225,000, compared with $416,900 for existing homes nationwide.

The Valley’s role in the U.S.-Mexico trade relationship has created thousands of jobs in the food business on the U.S. side of the border. Warehousing, packaging, and sorting shipments for dispatch by truck to every corner of the U.S. is an important part of the economy. At every border crossing, there are hundreds of trucks standing by: only a portion of Mexican trucks and truckers are certified to drive their loads into the American interior, after years of disputes over training and safety standards, and over the opposition of U.S. trucking interests.

In the old downtown of Hidalgo County’s seat, Edinburg, I visited the county judge, Richard Cortez. He says like many border elected officials, he is still waiting to see what the fallout from tougher border enforcement and new tariff regimes with Mexico will mean for his county, but he still likes where Hidalgo finds itself at the beginning of this new Trump era.

“We’re unique. We are on an international border with Mexico, which is Texas’s largest trading partner. One of America’s largest trading partners. We’re bicultural. We’re next to the Gulf of Mexico, so we have access to seaports. We’re positioned almost right smack in the middle of the Northern Hemisphere, between North America and the Southern Hemisphere.

“We’re able to grow with fertility and migration. We attract migrants to this area, and the whole world and the United States for sure is having problems reproducing itself, keeping up with population growth. Economists tell us we can’t sustain our economy without immigrants, much less grow our economy. So being attractive to people is a plus.”

Watching for Effects of Tariffs and Enforcement

“Judge” is an unusual Texas title. The holders do act as judges, but at the same time, as chief executives for their county, with significant administrative, managerial responsibility. With a long history as an elected official here, Cortez draws on both deep roots in Hidalgo, and, at 81, long life experience of this corner of Texas. Before NAFTA, he recalls, it was not unusual to see unemployment rates of 20% and more in Rio Grande Valley communities. “A lot of our commerce is centered around cross-border trade. We certainly have benefited from that.”

Cortez said it is hard to predict the effect of the twin earthquakes in his community with the arrival of President Trump’s second term. First, the on-again, off-again tariffs. Second, the possible repercussions of tougher enforcement and reduced movement on the border. “The first thing I would ask my president is, ‘Why?’ What are you trying to accomplish?” Judge Cortez said he understands the stated reasons for much tougher border enforcement: drug interdiction. “We’re trying to recruit companies here that need suppliers of goods and services that come from Canada and Mexico.” If some threatened tariffs actually become reality, “We just added 25% by bringing an item to America and usually that’s not a good thing.”

As for the many thousands of people who are his constituents, but could not enter a voting booth to support him, the judge gives a reply reflecting wide sentiment in the Rio Grande Valley. This is a subtle challenge. “We grew up here on the border when you would go to Mexico and come back and it was like going across the street. It wasn’t any big thing. It was a friendly thing. A lot of us have families on both sides. People would come here to work and then go back to Mexico, and a lot of us would go to work in Mexico and come back over here.

“A lot of that has been interrupted. I’m told that we have over 100,000 people who are not here legally. OK, they’re not here legally. Many of them have been here for quite some time, and many of them are married and have children who are Americans. They’ve become part of our economy, our workforce. The fear of them getting deported is a scary thing for us, even though we know the laws should be enforced. There’s no argument about that. But how do you find pleasure in taking a father or a mother away from a household and deporting them back to a country they are probably foreigners to now?”

Navigating Around Immigration Law

Judge Cortez noted that there has not been substantial immigration law passed by Congress in almost 40 years, since the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986. He calls current law “antiquated,” and echoes the complaint sounded by immigration advocates nationwide, that enforcement should be focused on serious criminals, not law-abiding workers who make his local businesses thrive.

These questions seem different from the back seat of a Border Patrol SUV, threading its way along a bluff overlooking the Rio Grande, made muddy by torrential, unseasonal rain. Officers in their distinctive green uniforms point out the massive fortifications, high fences, barbed wire, and surveillance equipment. Mexico is not in some far off, remote distance. There is no broad cordon sanitaire between the two nations. Mexico is right there. One veteran officer, Ryan Kaspar, points to the top floor of a nondescript building overlooking the border barrier on the Mexican side, just a few hundred feet from where we’re standing. “That’s a cartel lookout. From there, they can pretty much see everything we’re doing along this section of the river. They use that position to coordinate where and when they try to move people across the border.”

I look at the window. The short bridge overhead that separates the official crossings overseen by Mexican and U.S. officers. Tilt your head down and there’s the Rio Grande. Even after the heavy rains, not much more than a narrow, muddy ditch in this sector. Just to the other side of the formidable concrete barrier and steel fence is a broad green field, and a Burger King. The officers said cartels will try to move a large group of crossers all at once, and tell them to scatter as they run for it across that expanse of green. Often, there is a pre-arranged ride waiting for them at the Burger King. The successfully smuggled crosser will then make their way inland to a waiting job or family members, and hope to avoid the checkpoints up to 100 miles away from the international boundary.

How the Unique Geography Shapes Commerce and Culture

Perhaps expected, if not at this intensity, Spanish fills the air. You are greeted in shops and restaurants in Spanish first. The language of commerce from the biggest big-box retailer to the smallest coffee counter is Spanish first, but English is also spoken for those who prefer or cannot accomplish their business in this region’s original European language. Turn on the radio. As you search across the dial, most stations speak Spanish, with FCC-required identifications at the top of the hour in English, and often little else. DJs provide patter that seamlessly switches between Spanish, spoken along the Rio Grande since the 16th century, and English, proclaimed the official language of the United States by presidential order just this March.

Perhaps expected, if not at this intensity, Spanish fills the air. You are greeted in shops and restaurants in Spanish first. The language of commerce from the biggest big-box retailer to the smallest coffee counter is Spanish first, but English is also spoken for those who prefer or cannot accomplish their business in this region’s original European language. Turn on the radio. As you search across the dial, most stations speak Spanish, with FCC-required identifications at the top of the hour in English, and often little else. DJs provide patter that seamlessly switches between Spanish, spoken along the Rio Grande since the 16th century, and English, proclaimed the official language of the United States by presidential order just this March.

There is also a “border accent,” a variety of English with a Spanish lilt, not English spoken as a second language, with the accent of a language learner, but English as a first language infused with the vowels and cadences of Spanish lurking in the conversation. If you listen closely, it is very easy to hear.

Proximity to Mexico has always shaped both the culture and economy of this part of Texas. Austin, the capital, Dallas, the northern metropolis, and even Houston, the increasingly diverse immigrant port of entry and one of the country’s largest cities, all seem a world away from the palm tree-lined streets of Starr and Hidalgo. A hundred years ago, irrigation made it possible to turn a line of dusty little towns into a productive citrus belt, connected by new rail links that brought product to market.

Changes Since Inauguration Worrying Residents

Sharon Alexander walked away from a career as a corporate reorganization lawyer and went to seminary. Now, after decades away, she came home to Hidalgo County, where she grew up, to pastor a small church in Edinburg. “The culture hasn’t changed. It’s a frontier culture. A Norteño culture,” that is, a culture like that of northern Mexico, “It’s not like Phoenix, or Tucson, or San Diego. It’s a very distinct culture.” When she left the Valley in the late ’70s, she said, it was a sleepier place. More farms, more citrus groves, and white Texans unquestionably in power, and in charge.

The land is still home to farms, the rail lines, and the produce houses that clean, sort, and ship grapefruit, watermelon, cabbage, onions, and oranges. NAFTA and USMCA, the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement that succeeded NAFTA in the first Trump administration, have also made McAllen an important port of entry for Mexican fruits and vegetables. Spend any time at the border and it is easy to see what decades of supply chain integration have brought to the U.S. and Mexico.

The Rev. Alexander said over time, the changes have been empowering for Hispanics. “There are tons of first-generation college graduates now. We need a more diversified economy for them to make their lives here. If you finish law school, you end up doing title work, not sophisticated corporate work. There’s not enough here, yet, to pull people with advanced degrees, even those with family here.” She worries, like Judge Cortez, about the possible severity of immigration enforcement. “Life is getting more difficult and less secure. People are starting to worry about what’s happening. That’s what I’m seeing since the inauguration.

“There have been ICE raids, streets blocked off, officers in ski masks.” At UT Rio Grande Valley, “International students are scared for all kinds of reasons. Students who came with family don’t know whether their visas are going to get cancelled,” Alexander said.

Judge Cortez concerns are more basic. “Absolutely, we need the brains, the educated. Absolutely, we need all those people, and economists will tell you that if you want to grow your economy, grow your human capital. The average plumber and electrician in America is 56 or 60 years old. And you know what? I can’t fix my plumbing. I can’t fix my electrical service.” In the Valley, these jobs are heavily occupied by men from Mexico. Worried about plans he hears floated from Washington and Austin about a qualifications test to attract more highly educated immigrants, he dismisses the idea. “Who, if you’re in the hospital, and somebody needs to clean your poop, who is going to do it? A college graduate?”

Ray Suarez is the author of the book We Are Home: Becoming American in the 21st Century.